47 Years (or, Thoughts on Retirement)

“Who was the first man to look at a house full of objects and to immediately assess them only in terms of what he could trade them in for in the market likely to have been? Surely he can only have been a thief.”

– David Graeber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years

I have been on this planet for 32 years. That is the equivalent of two thirds the amount of time a working adult will spend laboring in their life. Sort of.

Not everyone lives a full life and not everyone needs to work to support themselves. Here in Canada, people can retire at any time, but most are compelled to a decision between the ages of 55 and 70. The vast majority spend ages 18 to 65 chasing the dream of freeing themselves from labor. A reprehensible 47 years. Not reprehensible because of what they are doing, choosing to do, or the fact that they are working. There is nothing inherently wrong with work, with occupying yourself in a profession to serve yourself or others, or with finding value in it. Reprehensible, then, because nearly all who work do so primarily to survive – to ensure basic needs, pay off debts, support others, or secure a modicum of leisure. Participate or suffer.

But I digress. This particular post is not about that aspect of how we set up our economy. Instead, it is a rumination on retirement. The end goal. Call it what you will.

I am 14 years into my 47 (or more likely, 52 or more). The sad truth is that retirement may be a fantasy for many individuals moving forwards. There are a variety of statistics that confirm how little Canadians are saving, or how many are aware of how little they are saving, or of those foregoing retirement because they must. Fewer and fewer are earning enough to afford the fast-rising costs of homes; the biggest chunks of paychecks ending up in the pockets of landlords small and large. Increasing inequality, unfettered inflation, reliance on resources dwindling our breathable air, and a financial system that incentivizes greed and excessive growth, not helping in the slightest.

Of course, with a social welfare system that hedges the worst outcomes, Canadians are fortunate. More fortunate than most in the world who have no vision of an old age free from labor, enjoyed on sunny beaches and shimmering shores. There is something to be said for selling your life and soul for a limited time rather than having it wrested from your grip as a child never to get it back.

And I am one of the fortunate ones. Lucky enough to have had the support network to pursue education to a graduate level. Lucky enough to have secured employment not soon after, to have paid off debts in part because I did not have to worry about the costs of rent or food while I searched for work. Lucky enough to have spent nearly half of those 14 years not laboring, able to rely on financial and emotional supports that are a luxury for many. A clear example of inherited wealth (monetary and otherwise) – of privilege neither realized nor forsaken – so that I can be in a position to even contemplate retreat from the reprehensible.

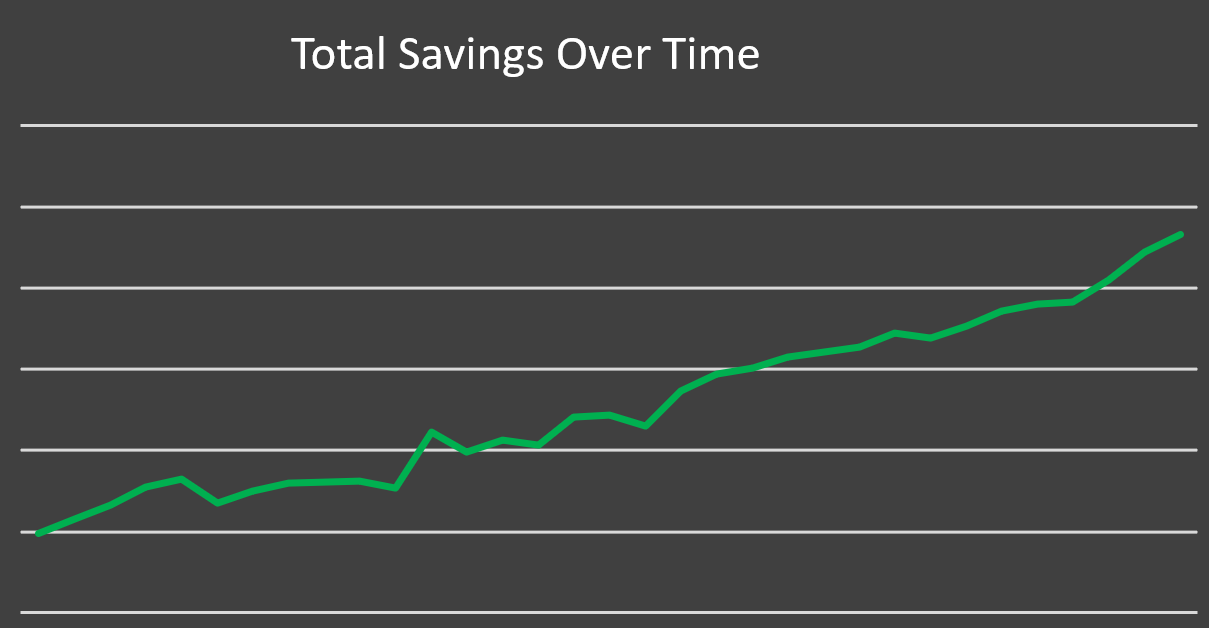

So here I am, tax season approaching, going over my contributions towards various accounts and staring at the trajectory of all those infernal lines that go up and down, determining our collective fates. Caught up in the narrative, trying to calculate what will be needed to secure a stable future in an immoral environment.

– – –

Invest in the Future by Burning It

We are told to save early and save often. Putting away small amounts monthly early in adulthood can put you a million dollars ahead of someone who saved with the same frequency and with much larger amounts later in life. The principles of basic math, compound interest, at work. Sure, throw money into a savings account, but that means you lose money over time. The interest rate will be paltry compared to inflation. Buy things that appreciate in value – a house, perhaps.

But no, the fastest way to assure financial security and ride the volatile wave of market madness is to invest. “Grow” your money on the proverbial tree of financial speculation. If you are in Canada, this equates to stockpiling in your bank- or brokerage-managed Mutual Funds, Tax Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs), Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs), Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs), First Home Savings Accounts (FHSAs), Registered Disability Savings Plans (RDSPs), Bonds, Guaranteed Investment Certificates (GICs), Margin Accounts, etc. Or you could just set up your own trading account and manage your investments assuming you have the time and knowledge to do so.

We are also told that, evidence aside, you should invest in portfolios managed by licensed financial advisors and firms. Their knowledge and experience a safeguard against drastic and unpredictable fluctuations that may diminish savings of all those chumps tying themselves to the market. (Fun fact about those chumps – they are all of us. There is no concealed truth in the market – we all do well or none of us do well; in the global arena, debt and suffering is piled where it always has, on the shoulders of the poor). But even if you do not trust the professionals, you can still rest easy – an online brokerage will take your money, bill you less, and afford you the same possibilities.

There is a lot more to say here about the snake oil state of the financial industry – a conglomerate of modern astrologers settled atop a house of cards that has repeatedly fallen down. But there is a reason I left studying this stuff behind. (Seriously, just put your money in index funds with low fees and forget about it. The low fees will ensure the indexes outperform the best managed funds over the long-term.)

And that gets us to the rub: investing is a cornerstone of the retirement rubric. If you do not invest, you are left behind. The value of currency itself and the foundation of all our modern wealth is speculative, so putting the cash away does nothing. Buy in or get sold out. You must place your trust in an industry of professional gamblers or become one. There are very few out there who have the time, ability, and privilege to be able to trade their own stocks, options, and assets to build their wealth. Even fewer who do so ethically. The rest of us must go on with our day jobs and put our capital into pre-selected portfolios.

Which is a shame, because to invest in indexes or managed funds undoubtedly means giving money to the richest companies and people in our world. The largest contributors to increasing inequality, global pollution, business and ethical malpractices, and oppression of the marginalized. All my investment accounts, for example, are classified as ‘socially responsible’. In a sane world that accords itself in alignment with basic ethical principles, these terms and their definitions would preclude investments in fossil fuel corporations, war profiteers, arms groups, or say, mining companies at the heart of conflicts across Latin America. But in our world, ‘socially responsible’ means nothing. Greenwashing is rife, ‘responsible’ companies continue to act in bad faith, and the penalties for being caught are simply operational costs.

I challenge readers with investment accounts to take a closer look at them. Open up the latest statement, scroll down to the long list of acronyms representing companies, and google a few of them. How many are you comfortable supporting? How is it that this blind support of corporations responsible for greying the air and our collective morality is so commonplace? How dare it be so intrinsically tied to the very livelihoods and futures it is destroying?

– – –

Taking Stock

Thus, we are expected to devote our lives to work, and pledge the money we make to worst that our economies have wrought. Of course, our wealth grows, but the true cost of that growth may be likened to a mundane evil. The logarithmic graph possibly not trending in the direction we think or as drawn up in fancy financial charts.

As mentioned, costs do not rise linearly but geometrically or exponentially. I had mentioned rent earlier – my retirement assumptions include no home ownership and comically high estimates for a one-bedroom rental. Some other assumptions:

- Lack of inheritance (as a matter of principle, but also: the market is indiscriminate and financial difficulties shall be shared by all),

- Wages will not keep up with rising costs (no need to give me a Nobel for figuring that out),

- Basic necessities like food and healthcare will become more expensive as I age,

- Modern political economies are unsustainable and thus, the future will bring expected, repeated, collapses of global markets, and

- Conflicts and tragedy driven by climate change and inequality will rise.

Some may argue, but the climate and inequality points are fundamental to understanding the formulation of future wealth. No one will escape the direct and indirect consequences of unmitigated exacerbations in either of those arenas.

As a result of the above meditation, I like so many others, monetize life. Trying to keep the numbers ticking in a positive direction, feeling frustrated at the effort it would take to seize the reins and invest capital towards my own ends. It is a sick way of viewing the world, as Graeber alludes to in the quote atop this post. But we are all in a shared sickness, and we are well capable of beating it.

As Graeber himself affirms in The Utopia of Rules: “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”