Bringing the Factory to the Farm

A morsel of your time, if you please, to dive into a surreal vision. A moment under the darkening firmament with a gaggle of green learners, rendered speechless by the immutable.

– – –

A late evening in July 2013. My colleague and I have just finished a day’s worth of sessions at a school a couple of kilometers from the homestead where we are residing. This is a joint elementary-secondary, about 7 clicks away from the small but busy village center of Busolwe, Eastern Uganda. We have supported facilitating a set of reading, writing and debating competitions to close out our time at this particular location. Part of a community-led program to foster higher literacy rates and championed by the local library and Elder Council.

Our host and supervisor, the local librarian, has left us and returned home for the night. We are to finish our conversations and join him and his family for dinner at a reasonable time. The kids, of course, have to stay. They live at the school most of the year, sleeping in dense rooms in stacked beds, sharing meals in the same rooms where they study. They do the chores too – some have already started sweeping the hallways in preparation for mealtime. The teachers, who double as caretakers, and most of whom have not been paid for many months, have retired to their quarters or trundled home.

I am speaking with a few of the older students trying to convince them of impossibilities. Most of the teens have not travelled too far down the dirt roads that divide up the surrounding farmlands. The majority of their time is spent eating, sleeping, learning, praying, playing, cleaning, cooking, and digging. Yes, digging. For when they are at home and away from the pressures of attending class, to get an education so they can be 1 of 30,000 applicants for an entry level position in Kampala, many are expected to wake up at 5am to dig. Laboring away for their guardians so that the crops can be sown, minded, and reaped. At least it has not rained in several days, or enswa would be littered everywhere, the children absent as they harvested the water-escaping delicacies emerging from the Earth.

Enswa wings. Enswa are winged termites referred to as “white ants”.

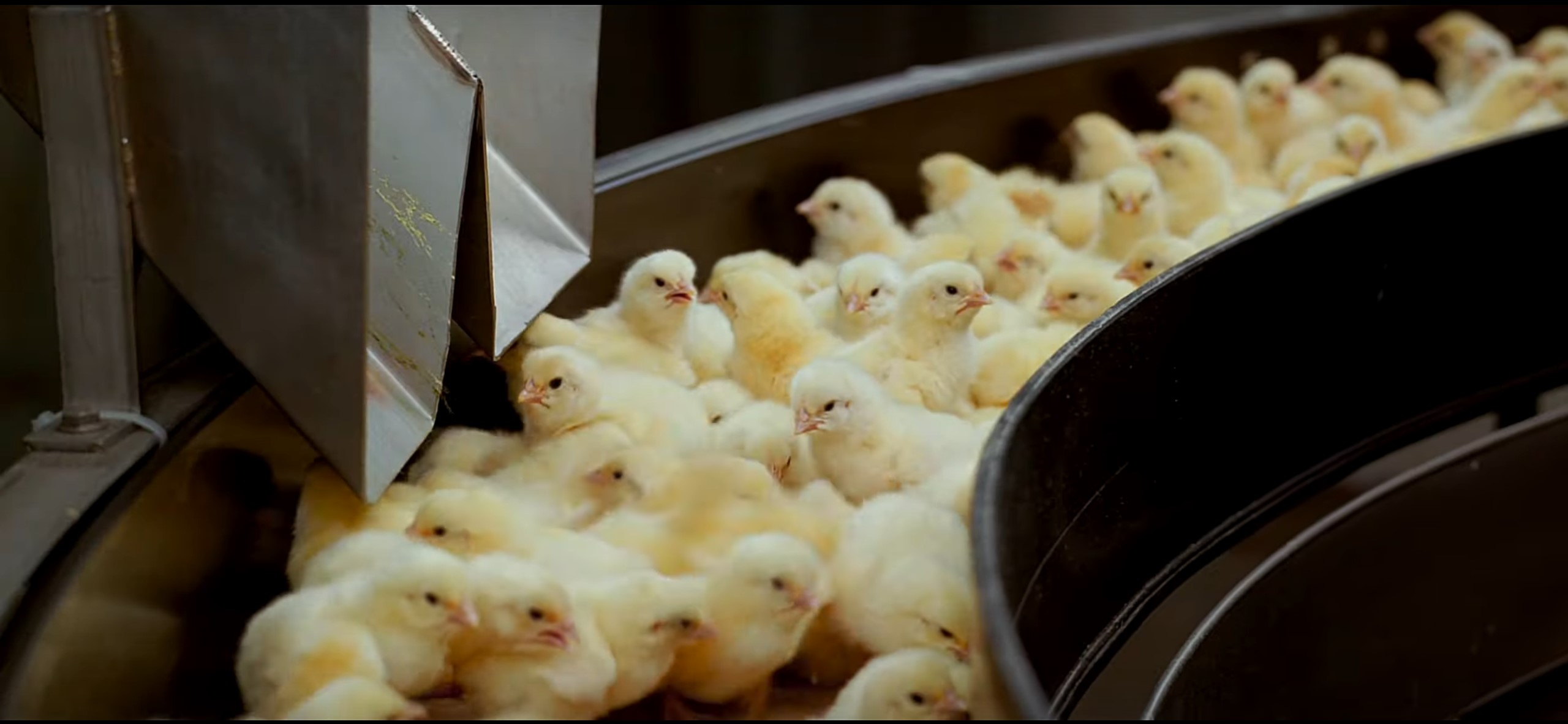

Our discussion, which started on the topics of our daily lives, has somehow narrowed to factory farms. We are all seated in the grass by a large tree with our bags strewn nearby. Some of the children have become bored by us and have headed off as a few of the brighter stars and planets are unveiling themselves. The ones that stay are not buying it. Rows of cows in steel contraptions with their udders attached to pipes, conveyed along as their milk is drained into large vessels for processing? Chickens caged so tightly that they regularly suffocate, with blunted beaks so they do not peck each other to death? Pigs having their tails docked before being shocked and boiled alive? Animals being force-fed so they balloon in size before being killed in adolescence at four times the size of their natural adult state? Balderdash. How can these things be normalized or even possible?

The creatures that these youngsters see on a daily basis are some of the most fortunate livestock on Earth. They roam free, feed on the land, live to adulthood, and are not tortured or mutilated on an hourly basis. The last true farm animals. So they cannot believe what I am saying – perhaps in small corners of the sickest parts of the world, but the basis of global food systems? Inconceivable.

Somewhere in between the baffled snickers and incredulous looks, I realize some evidence is at hand. I stroll over to my bag, bring out my laptop and locate a video. It is one of a few dozen that I downloaded in advance of the summer, knowing I would not have internet and wanting to have some entertainment accessible if desired. I click ahead to around the 45min mark. Flashes of busy intersections in New York, Tokyo, cigarette factories, a gargantuan mosque – I know it’s here somewhere. People bustling through metro stations to quickening musical beats; a sharp cut to a man whirring an electrical component on an uncovered circuit board, then doing the same again and again in accelerated footage, clearly for hours on end; this is enough to hush the kids and elicit a few gasps.

But then the images arrive. The dozen or so students around us have now leaned in and are closely observing. Their rapt expressions painted with horror. Hundreds of eggs are collected in swirling metallic implements, then organized with precision. CUT to hundreds of people rushing through rotating glass doors and up/down escalators. CUT to newly hatched chicks loaded onto conveyor belts and sorted with disregard by expeditious laborers. CUT back to those commuters, squeezing themselves out of trains. CUT to further interspersed montages of the chicks on belts and the masses in transit. CUT to the rejected chicks falling down a chute to their ends. CUT to the unlucky ones, tagged in one clip and having their beaks unceremoniously burnt to remove their stings in another. CUT to grown chickens confined to endless queues of cages inside a large, darkened warehouse, their bodies colorless in every respect but effulgent under the camera’s light. Innocent but doomed. And finally, the cruel sequence ends as we slowly look out a window at a timelapse of a traffic corridor in a busy urban environment, the cars mere ants, the lights of the city brightening as the background sounds die down to a hum.

Credit: Magidson Films

The night has completely arrived and there are voices calling the students back to their humble dorms. I close the laptop and share that this is only a small window into modern treatment of animals. I tell them the name of the film, Baraka, though I have no idea if they will ever have a chance to see it again. I wish I could share more, or show them the rest, but time has run out. I am not sure what impression it has made on them or if it will resonate. My colleague and I pack up, wish everyone a pleasant evening, exit the courtyard onto the dirt road, and walk back to the homestead.

– – –

Kids are pretty good at spotting the inhuman. Adults are pretty good at suppressing and hiding it.

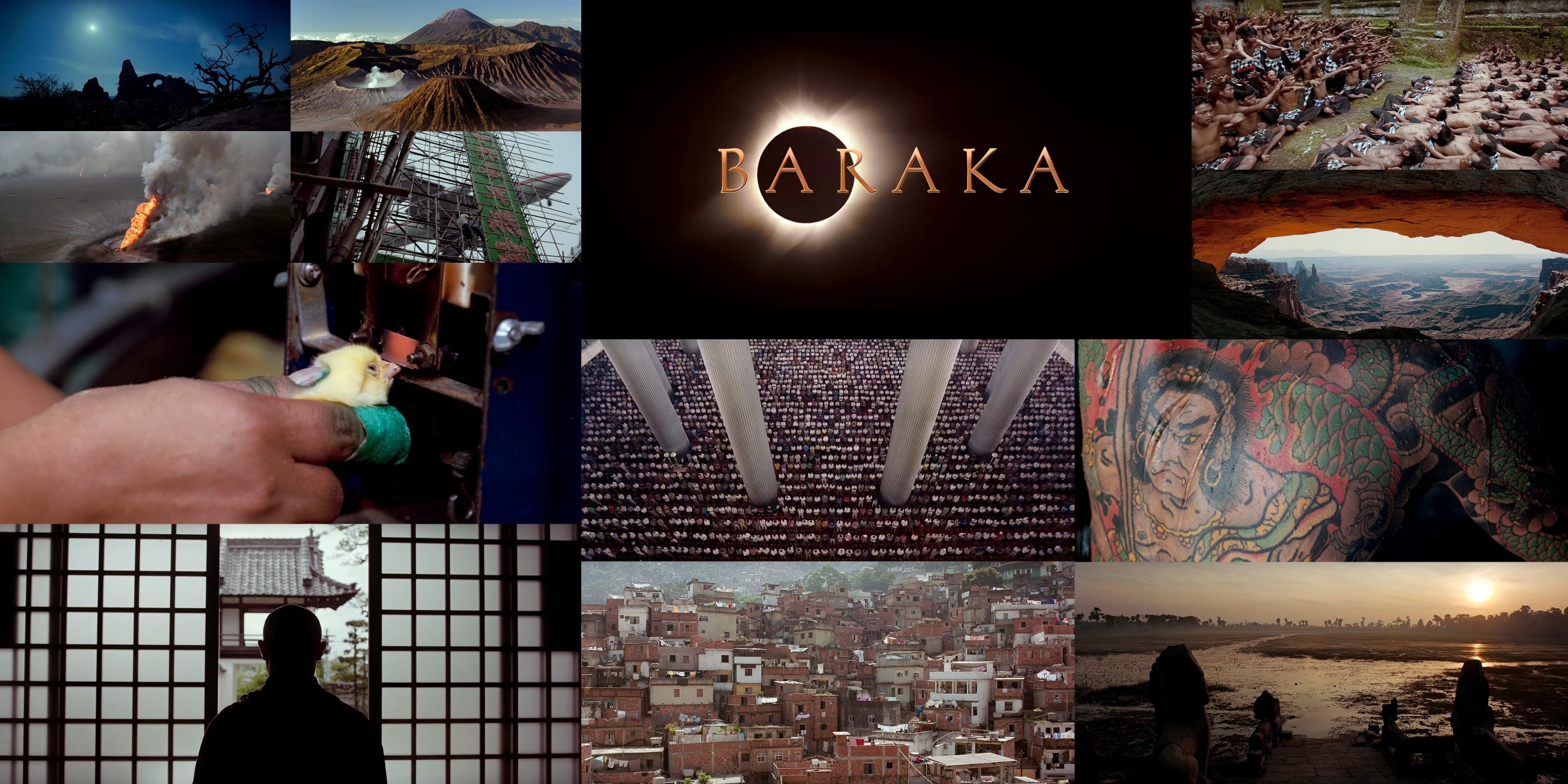

1992’s Baraka is a triumphant film. It was created by documentarian Ron Fricke, who also served as cinematographer on its spiritual predecessor, 1982’s Koyaanisqatsi. An arrangement of score and scenes like no other, Baraka is a meditation on the natural, its veneration, and its perversion.

And, as I have hopefully illustrated, a film that can relate people from different walks of life by showcasing the dread and delight at the heart of the routine. So often consumed yet so rarely experienced. Good documentaries do not only divulge unsavory and unrealized truths, but they also animate their audience. Baraka does this with aplomb, using an audiovisual dialectical montage without any narration, to stoke in the viewer an inescapable apprehension. There are many films that use similar styles and structure themselves in more candid or blunt ways. But Baraka has a special place in my memories.

The film stretches from the quietest corners of the highest mountains to the raucous nucleuses of civilization. It takes time to pause on singularly felt moments of isolation before casting us into rituals that unite billions. Illuminating the universally visible but hardheartedly ignored to the desperately hidden and foolishly forgotten, the film is an unflinching capture of our planet at the turn of the millennium. It lingers on the uncomfortable as well as the fantastic, managing to introduce depth through non-narrative framing. Particular standouts are the large number of people who we are immediately drawn to – staring at nothing, eyes glazed over as they attend to the mundanities of their lives. Or the vertigo-inducing shots of landscapes from unique viewpoints, often the result of erosion or processes over eons, slotted between deposits and destruction resulting from human consumption.

Perhaps the most satisfying aspect of the film, its ability to connect people in fascination and bemusement. Students in dialogue, two from universities in urban Canada and a dozen from secondary in rural Uganda, being equally engrossed in the same scenes, from two very distant experiential and philosophical nodes. Commoners from alien corners recoiling from and being drawn to the same stark imagery in equal measure. Not to say that Baraka is unique in its transcendence of cultural idiosyncrasies, but it accomplishes the feat in an exceptional manner.

My entry for today: a curious memory fashioned spontaneously in shadow. Facilitated by an inimitable film that helped bring the world into a 13×9 inch rectangle that seemed larger than life for a few short moments to those who viewed it.