Weekly Picks – June 9, 2024

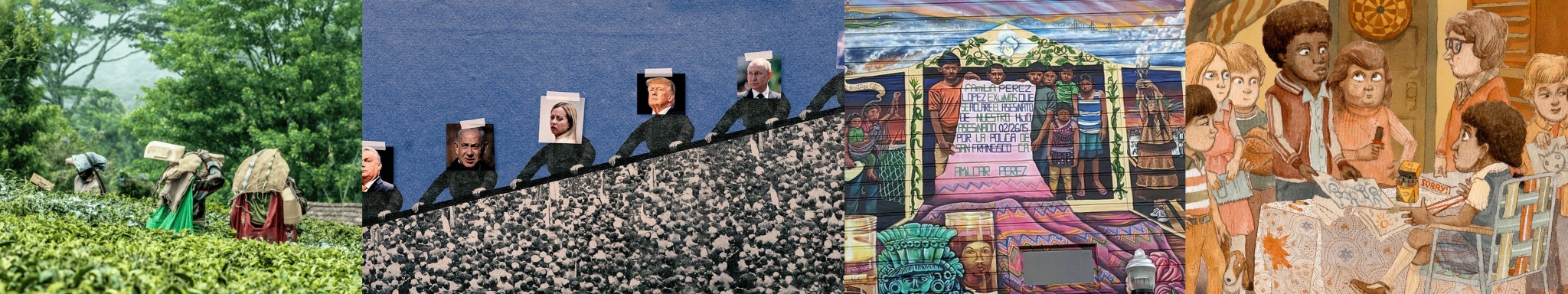

Credit (left to right): Aboodi Vesakaran; Project Syndicate; A section of the mural Alto al Fuego by Juana Alicia / Mauricio E. Ramirez / Public Books; Current Affairs

Credit (left to right): Aboodi Vesakaran; Project Syndicate; A section of the mural Alto al Fuego by Juana Alicia / Mauricio E. Ramirez / Public Books; Current Affairs

“‘There are decades where nothing happens,’ Lenin wrote, ‘and there are weeks where decades happen.’ The last eight months have seen an extraordinary acceleration of Israel’s long war against the Palestinians. Could the history of Zionism have turned out otherwise? Benjamin Netanyahu is a callow man of limited imagination, driven in large part by his appetite for power and his desire to avoid conviction for fraud and bribery (his trial has been running intermittently since early 2020). But he is also Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, and his expansionist, racist ideology is the Israeli mainstream. Always an ethnocracy based on Jewish privilege, Israel has, under his watch, become a reactionary nationalist state, a country that now officially belongs exclusively to its Jewish citizens.” (Adam Shatz, “Israel’s Descent”, LRB Vol. 46 No. 12)

This week’s collection:

- Israel’s Descent

- Finding Sanctuary in Art

- Stories Are Weapons

- The Possibilities for Child Liberation

- The New-Old Authoritarianism

- Don’t Major in English: And Other Bad Advice from the World

- Migrating Workers Provide Wealth for the World

Introductory excerpts quoted below. For full text (and context) or video, please view the original piece.

“When Ariel Sharon withdrew more than eight thousand Jewish settlers from the Gaza Strip in 2005, his principal aim was to consolidate Israel’s colonisation of the West Bank, where the settler population immediately began to increase. But ‘disengagement’ had another purpose: to enable Israel’s air force to bomb Gaza at will, something they could not do when Israeli settlers lived there. The Palestinians of the West Bank have been, it seems, gruesomely lucky. They are encircled by settlers determined to steal their lands – and not at all hesitant about inflicting violence in the process – but the Jewish presence in their territory has spared them the mass bombardment and devastation to which Israel subjects the people of Gaza every few years.

The Israeli government refers to these episodes of collective punishment as ‘mowing the lawn’. In the last fifteen years, it has launched five offensives in the Strip. The first four were brutal and cruel, as colonial counterinsurgencies invariably are, killing thousands of civilians in retribution for Hamas rocket fire and hostage-taking. But the latest, Operation Iron Swords, launched on 7 October in response to Hamas’s murderous raid in southern Israel, is different in kind, not merely in degree. Over the last eight months, Israel has killed more than 36,000 Palestinians. An untold number remain under the debris and still more will die of hunger and disease. Eighty thousand Palestinians have been injured, many of them permanently maimed. Children whose parents – whose entire families – have been killed constitute a new population sub-group. Israel has destroyed Gaza’s housing infrastructure, its hospitals and all its universities. Most of Gaza’s 2.3 million residents have been displaced, some of them repeatedly; many have fled to ‘safe’ areas only to be bombed there. No one has been spared: aid workers, journalists and medics have been killed in record numbers. And as levels of starvation have risen, Israel has created one obstacle after another to the provision of food, all while insisting that its army is the ‘most moral’ in the world. The images from Gaza – widely available on TikTok, which Israel’s supporters in the US have tried to ban, and on Al Jazeera, whose Jerusalem office was shut down by the Israeli government – tell a different story, one of famished Palestinians killed outside aid trucks on Al-Rashid Street in February; of tent-dwellers in Rafah burned alive in Israeli air strikes; of women and children subsisting on 245 calories a day. This is what Benjamin Netanyahu describes as ‘the victory of Judaeo-Christian civilisation against barbarism’.

The military operation in Gaza has altered the shape, perhaps even the meaning, of the struggle over Palestine – it seems misleading, and even offensive, to refer to a ‘conflict’ between two peoples after one of them has slaughtered the other in such staggering numbers. The scale of the destruction is reflected in the terminology: ‘domicide’ for the destruction of housing stock; ‘scholasticide’ for the destruction of the education system, including its teachers (95 university professors have been killed); ‘ecocide’ for the ruination of Gaza’s agriculture and natural landscape. Sara Roy, a leading expert on Gaza who is herself the daughter of Holocaust survivors, describes this as a process of ‘econocide’, ‘the wholesale destruction of an economy and its constituent parts’ – the ‘logical extension’, she writes, of Israel’s deliberate ‘de-development’ of Gaza’s economy since 1967.

But, to borrow the language of a 1948 UN convention, there is an older term for ‘acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group’. That term is genocide, and among international jurists and human rights experts there is a growing consensus that Israel has committed genocide – or at least acts of genocide – in Gaza. This is the opinion not only of international bodies, but also of experts who have a record of circumspection – indeed, of extreme caution – where Israel is involved, notably Aryeh Neier, a founder of Human Rights Watch.

The charge of genocide isn’t new among Palestinians. I remember hearing it when I was in Beirut in 2002, during Israel’s assault on the Jenin refugee camp, and thinking, no, it’s a ruthless, pitiless siege. The use of the word ‘genocide’ struck me then as typical of the rhetorical inflation of Middle East political debate, and as a symptom of the bitter, ugly competition over victimhood in Israel-Palestine. The game had been rigged against Palestinians because of their oppressors’ history: the destruction of European Jewry conferred moral capital on the young Jewish state in the eyes of the Western powers. The Palestinian claim of genocide seemed like a bid to even the score, something that words such as ‘occupation’ and even ‘apartheid’ could never do.

This time it’s different, however, not only because of the wanton killing of thousands of women and children, but because the sheer scale of the devastation has rendered life itself all but impossible for those who have survived Israel’s bombardment. The war was provoked by Hamas’s unprecedented attack, but the desire to inflict suffering on Gaza, not just on Hamas, didn’t arise on 7 October. Here is Ariel Sharon’s son Gilad in 2012: ‘We need to flatten entire neighbourhoods in Gaza. Flatten all of Gaza. The Americans didn’t stop with Hiroshima – the Japanese weren’t surrendering fast enough, so they hit Nagasaki, too. There should be no electricity in Gaza, no gasoline or moving vehicles, nothing.’ Today this reads like a prophecy.”

“What do refugees and migrants seek? I ask this question amid the ongoing crackdown at the US border, a crackdown that appears to be unceasing and indefinite. Migrants and refugees share commonalities in their pursuit of new lives. Their journeys are often fraught with risk and uncertainty, encompassing dangers along migration routes, potential encounters with law enforcement, and uncertain futures. Ultimately, their common thread is a desire for safety, whether seeking better opportunities or refuge from specific threats or persecution in their home countries. What they seek is a space for refuge, a place for safety: sanctuary.

In this article, I contemplate how a single mural honors Latinx victims of police violence both at the US border and in US cities. In so doing, this mural invites viewers to learn about the past, while contextualizing their narratives. Taken together, this mural—Alto al Fuego en La Misión, which translates to “Ceasefire in the Mission” (figure 1)—demonstrates the pivotal role that art activism plays in healing and in fostering future potentialities.”

“The positivity industry has repurposed Joan Didion’s best-known quote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” into a self-help maxim. The sentence encapsulates Didion’s belief that “we live entirely… by the imposition of a narrative line” on our lives. Narrative, she maintained, is how we manufacture meaning from the welter of our experiences, the chaos of our thoughts.

Didion’s explanatory narrative about our explanatory narratives has become an explanatory meta-narrative. The necessity of “storifying” your “messaging” is now TED-talk orthodoxy, popularized by Malcolm Gladwell’s pop-neuroscience parables and given scientific legitimacy by evo-psych titles like The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human by Jonathan Gottschall. On YouTube, the algorithm serves up a promo video for the screenwriting guru Robert McKee’s “STORY Seminar” (yes, all caps). “When the storytelling goes bad in the culture,” McKee intones portentously, “the result is decadence… the tide of negative culture, I think, you know, bad, false, empty lies, is almost overwhelming us.”

“We tell ourselves stories…” is the opening sentence of Didion’s essay “The White Album,” a morning-after meditation on the cultural chaos of the ’60s. It was a moment much like ours: belief in institutions, from government to science to law enforcement to SCOTUS to democracy itself, was fast eroding. It was a time, wrote Didion, “when I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself.” Maybe that’s why her quote speaks to us. Our insistence on the power of storytelling comes at a moment of epistemological vertigo, when our faith in narrative truth is being swept away by a tide of lies.

Increasingly, however, we tell ourselves stories in order to lie. In Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind, Annalee Newitz chronicles and critiques the struggle for control of the mass imagination. A science journalist and founder of the SF and tech-culture blog io9, Newitz reads American history through the lenses of propaganda and psyops. They consider the weaponization of storytelling in today’s culture wars as well as in past propaganda campaigns to rationalize white supremacy and anti-Black racism, gin up moral panic over LGBTQ people, and justify the extermination of Indigenous peoples and the erasure of their cultures.”

4. The Possibilities for Child Liberation

“In 1972, a 13-year-old named Peter Cane launched a youth liberation group at his junior high school in Huntington, New York—and was quickly reminded of his reason for doing so when his efforts to rent a P.O. box for the group were mercilessly thwarted by the Greenlawn Post Office. There, Cane was told he would either “have to show proof he was 18 or come back with his parents.” So it goes, he explained to Newsday, in the “no-man’s-land” into which all youths come of age. It is a landscape characterized by extreme vulnerability, little legal recourse, and a thousand petty humiliations children must contend with between the post office, the primary school, and their parents’ house. “Our lives are considered the property of various adults,” explained an activist with Youth Liberation of Ann Arbor in an edition of the Ann Arbor Sun from the same year. “[But] we do not recognize their right to control us. We call this control Adult Chauvinism and we will fight it.”

Cane may well have been inspired by the unexpected success of Youth Liberation. Founded in early 1971, about six months before 18-year-olds were even granted the right to vote in the United States, the Ann Arbor group (and the wider movement it represented) followed on the heels of Civil Rights and second-wave feminism. It came, too, just a few years after the youth-helmed protests of 1968 shook the world. Youth Liberation was the brainchild of founders who were, legally speaking, children themselves: 15-year-old Keith Hefner and several friends, whose “modest goals” included “taking over the Ann Arbor, Michigan, public schools[…] and building a nation wide movement for youth civil rights” from Hefner’s parents’ basement. “If we happened to spark a nationwide uprising, as the youth of France had done just three years earlier,” Hefner quipped when he reflected on the movement in a 1988 essay, “so much the better.”

The group quickly made a splash in local politics, persuading the Ann Arbor City Council to retire outmoded curfew laws on the grounds that “any law which proposes to regulate a segment of the population on the basis of an unavoidable physical characteristic is inherently discriminatory and must be abolished.” They also attempted to run a ninth-grader in the 1972 election for the local School Board. Sonia Yaco’s campaign was thwarted by a state election law setting a minimum age requirement of 18 for would-be candidates, so she proceeded to file a lawsuit against the State of Michigan in the U.S. District Court in Detroit. This failed when the judge ruled that the age requirement was, in fact, necessary to “assure [sic] some measure of maturity” in elected officials—though Yaco still managed to snag 1,300 write-in votes. With youth liberation on the tip of everyone’s tongue, the School Board announced plans for Community High School: Ann Arbor’s very own experimental “school without walls,” which maintains a radical social and political activist bent to this day.

Despite these direct and indirect victories, however, youth activists were dogged by disbelief. A 1976 article in the Asheville Citizen mocked Youth Liberation’s stance that “since Americans under the age of 18 can’t vote, they are subjected to ‘taxation without representation’ just as their forefathers were under King George III.” A 1974 piece in the Vancouver Sun, meanwhile, admonishes, “Let’s not insist… that day-old babies have credit cards. Let’s face it—some are simply not ready.” And a 1975 letter to the editor in the Los Angeles Times dismissed the movement’s other demands as follows: “We must allow our children complete ‘freedom’ to be run over by cars, be morally and physically destroyed by criminals, and seduced in cutting school and heisting banks by people who talk about ‘rights.’”

Attrition posed its own problems as the 1970s arced inexorably toward the 1980s. Gradually, many Youth Liberation members left town for college or graduated into other radical movements. A 1977 edition of the Detroit Free Press found 22-year-old Hefner—by then the last member of Youth Liberation of Ann Arbor standing—alone in the Youth Liberation HQ in his parents’ basement, contemplating early retirement from the cause. But the urgency of liberation for children, whom one ACLU lawyer referred to in 1974 as a population of “unseen people,” remains as immediate now as it was then. It is something every child knows—and adults would do well to remember.”

5. The New-Old Authoritarianism

“I use the term strongman for authoritarian leaders who damage or destroy democracy using a combination of corruption, violence, propaganda, and machismo (masculinity as a tool of political legitimacy). A strongman’s personality cult elevates him as both a “man of the people” and “a man above all other men.” Authoritarianism is about reorganizing government to remove constraints on the leader – which in turn allows him to commit crimes with impunity – and machismo is essential to personality cults that present the head of state as omnipotent and infallible.

Strongmen, as I define them, also exercise a form of governance known as “personalist rule.” Government institutions are organized around the self-preservation of a leader whose private interests prevail over national interests in both domestic and foreign policy; public office thus becomes a vehicle for private enrichment (of the leader and his family and cronies).

Personalist rule is associated with autocracies. A good example is Vladimir Putin’s Russia, where a kleptocratic economy allows for the systematic plundering of private and public entities for the financial benefit of the leader and his circle. Yet personalist rule can also emerge in degraded democracies when a politician manages to exert total control over his party, develop a personality cult, and exert outsize influence over mass media. That happened in Italy under Silvio Berlusconi (who owned the country’s private television networks and much more) and in America during Donald Trump (through his command of Twitter and his alliance with Fox News).

Because personalist leaders are always corrupt, they and those closest to them usually will be investigated when they come to power in a democracy. In such cases, governance increasingly revolves around their defense. More party and civil-service resources will be devoted to exonerating the leader and punishing those who can harm him, such as judges, prosecutors, opposition politicians, and journalists. In the United States, the Republican Party has lent itself fully to this personalist endeavor. The House Subcommittee on the Weaponization of Government, chaired by Trump loyalist Jim Jordan, is just one example of a government mechanism created for the sole purpose of targeting anyone who threatens the leader.

Even where investigating the leader is no longer possible, as in Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey, a formidable army of lawyers, trolls, bureaucrats, and others will sustain the leadership cult and watch for any cracks in the armor. Hence, the Turkish government spends considerable time and public funds pursuing tens of thousands of “insult suits” against Erdoğan’s critics.

Finally, while democratic leaders can be deeply flawed as individuals, the strongman’s corruption and paranoia ineluctably leads him to develop highly dysfunctional governance structures such as “inner sanctums” composed of sycophants, family members, and advisers chosen for their loyalty rather than their expertise. As a result, strongmen will gradually come to lack the proper objective input to make reasoned decisions. Their impulsive and mercurial personalities will make their cabinets a circus of hirings and firings, with the chaos further drowning out sound advice. Trump, who made his daughter and son-in-law top advisers, is in this lineage. “I’m speaking with myself, number one, because I have a very good brain and I’ve said a lot of things,” he said in 2016, when asked who advises him on foreign policy. When the strongman is ripe to be overthrown, he may be the last to know.”

6. Don’t Major in English: And Other Bad Advice from the World

“I often teach literature written during the Third Reich or the Soviet rule of Russia; I’m always inspired and moved by how much prisoners of concentration camps or the Gulags relied on poetry and literature to sustain them as they endured unimaginable horrors. They would recite from or compose verses to memory. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn would save bits of his bread ration to create rosary beads to mark lines of poetry, as he composed it, to aid his memory. In Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl credits the “inner self” or inward life as the source of survival for those in the concentration camps. Worn out by a seemingly pointless and endless future and a painful and depressing present, the prisoners must draw on their memories of the beautiful things they loved from the past to encourage them to keep living through the suffering.

How many of us, if we underwent such terrors and trials, or—let’s be less extreme—when we endure life’s regular crises of sickness, mourning, and anxiety, have the inner resources that we need to be sustained? What verses might we recite for moral sustenance? What immediately comes to my mind: “Look at this stuff. Isn’t it neat? Wouldn’t you think my collection’s complete? Wouldn’t you think I’m the girl who has everything?” Is anyone else afraid that the treasures of our hearts have been Disney-fied? Our very souls have been molded by the culture that we have consumed, and if we have not chosen wisely, we have been impressed upon with poor substitutes for culture. Would we not prefer to have other refrains in our heads and inscribed on our hearts? “The quality of mercy is not strained,” “All shall be well and all manner of things shall be well,” “Yet I do marvel at this curious thing: To make a poet black, and bid him sing!”

What do we love and what do we spend our lives loving? When we talk about education, we do so in such a sanitized way. People speak abstractly of making productive citizens. The language of consumers dominates. The use of market language undergirds everything: what’s the ROI (return on investment) of a course in humanities? What’s the value of studying ancient history? What’s the purpose of reading fiction?

. . .

Many people balk when I employ the word “useless,” especially when I use it to describe things we love, like great books. Or, most humorously to me, when I say—with all sincerity—that babies are useless. They get up in arms over it. “Babies can be used for cuddling,” they insist. And I refute them: “If you use my baby for your emotional support, you are mis-using my baby.” Or consider, what happens when that baby is not okay with such a use? When the baby is cranky, difficult, dirty, etc? We do not use babies, or people, or great books. Our culture conflates use with worth. Following the Industrial Revolution and the proliferation of utilitarianism…we assume that all things must be useful to be worthwhile…[W]e have set up the idol of use.”

7. Migrating Workers Provide Wealth for the World

“Each year, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) releases its World Migration Report. Most of these reports are anodyne, pointing to a secular rise in migration during the period of neoliberalism. As states in the poorer parts of the world found themselves under assault from the Washington Consensus (cuts, privatization, and austerity), and as employment became more and more precarious, larger and larger numbers of people took to the road to find a way to sustain their families. That is why the IOM published its first World Migration Report in 2000, when it wrote that “it is estimated that there are more migrants in the world than ever before,” it was between 1985 and 1990, the IOM calculated, that the rate of growth of world migration (2.59 percent) outstripped the rate of growth of the world population (1.7 percent).

The neoliberal attack on government expenditure in poorer countries was a key driver of international migration. Even by 1990, it had become clear that the migrants had become an essential force in providing foreign exchange to their countries through increasing remittance payments to their families. By 2015, remittances—mostly by the international working class—outstripped the volume of Official Development Assistance (ODA) by three times and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). ODA is the aid money provided by states, whereas FDI is the investment money provided by private companies. For some countries, such as Mexico and the Philippines, remittance payments from working-class migrants prevented state bankruptcy.

This year’s report notes that there are “roughly 281 million people worldwide” who are on the move. This is 3.6 percent of the global population. It is triple the 84 million people on the move in 1970, and much higher than the 153 million people in 1990. “Global trends point to more migration in the future,” notes the IOM. Based on detailed studies, the IOM finds that the rise in migration can be attributed to three factors: war, economic precarity, and climate change.

. . .

The treatment of these migrants, who are crucial for poverty reduction and for building wealth in society, is outrageous. They are treated as criminals, abandoned by their own countries who would rather spend vulgar amounts of money to attract much less impactful investment through multinational corporations. The data shows that there needs to be a shift in class perspective regarding investment. Migrant remittances are greater by volume and more impactful for society than the “hot money” that goes in and out of countries and does not “trickle down” into society.

If the migrants of the world—all 281 million of them—lived in one country, then they would form the fourth largest country in the world after India (1.4 billion), China (1.4 billion), and the United States (339 million). Yet, migrants receive few social protections and little respect.”