Embers of Empire

Allow us royal subjects, commonwealth citizens governed by neocolonial pressures, we who have lived through dying embers of empire and observed the revolving door of mediocrity in British politics over the last decade or so, our quiet judgments and tempered schadenfreude. With the approval of an ailing monarch, the Conservatives will finally find their way out of power in the next few days. Their replacements will wonder where to start; this election is not exactly a mandate-providing affirmation, rather a denouncement of what came before. The public did not chase an inspiring vision; they voted for the hope of basic competence. The unfortunate truth – a bittersweet relish – that we from afar can savor in a twisted way, is that there will be brevity in this grand feeling of change. A new team dominating the game does not necessarily change the sport being played.

– / – / –

A kingdom voted. Kingdoms tend not to hold too many consequential votes. Democracy is not a requirement under divinely blessed royalty. But this kingdom is United, you see. A constitutional monarchy, they say. It delegates freedom under colonial architecture; a parliament hardly parochial. Its subjects are free to exercise their voice – an inside voice, mind you. Nothing loud enough to disturb the foundations of those lovely palaces and their inhabitants, or a growing body of unelected nobility who specialize in slowing down legislation already outpaced by the most sluggish of snails.

This is not the land of brave trial-and-error politics, but one of rehashing failed ideas given cosmetic treatments. A country that has offered largely static views on economic and foreign policy for over four decades. In a time when large blocs of nations grappled with the right combinations of Keynesian, Marxist, or Monetarist ideas, the UK tried austerity… and nothing else. A reminder that the last Labour governments championed the Iraq war and continued the Tory project of privatizing health services to undermine the NHS. I wonder how long it has been since a party in power was actually sympathetic, in action, to the marginalized or the working class. And how much sympathy they elicited from the House of Lords or head of state.

But this may be a reflection of the populace. At least, the politically active, participatory factions. This foreigner and brief interloper observed a small ‘c’ conservative political landscape. People of all ages within the conglomerate territory appear risk-averse in their volitions. Whether it was through apathy, complacency, or fear of novel approaches. Even in Edinburgh – filled with youth and committed to a more liberal republican future – one could not escape the feeling that there were certain red lines that could not be crossed. Jeremy Corbyn’s name was all it took to send people into fits of anger, no attention paid to the myriads of scandals that followed those actually in power. The press system, dominated by tabloids, periodicals, and punditry apple-skin-shallow, reduced everything to soundbites and everyone to caricatures. Complex narratives were impossible to find in the mainstream.

This day, and this particular installment of a Labour steward of the kingdom, dates back to the summer of 2016. Since then, six Prime Ministers have found themselves at 10 Downing Street in the span of eight orbits. When your leadership’s turnover rate rivals that of the Italians, you know you have a problem.

– / – / –

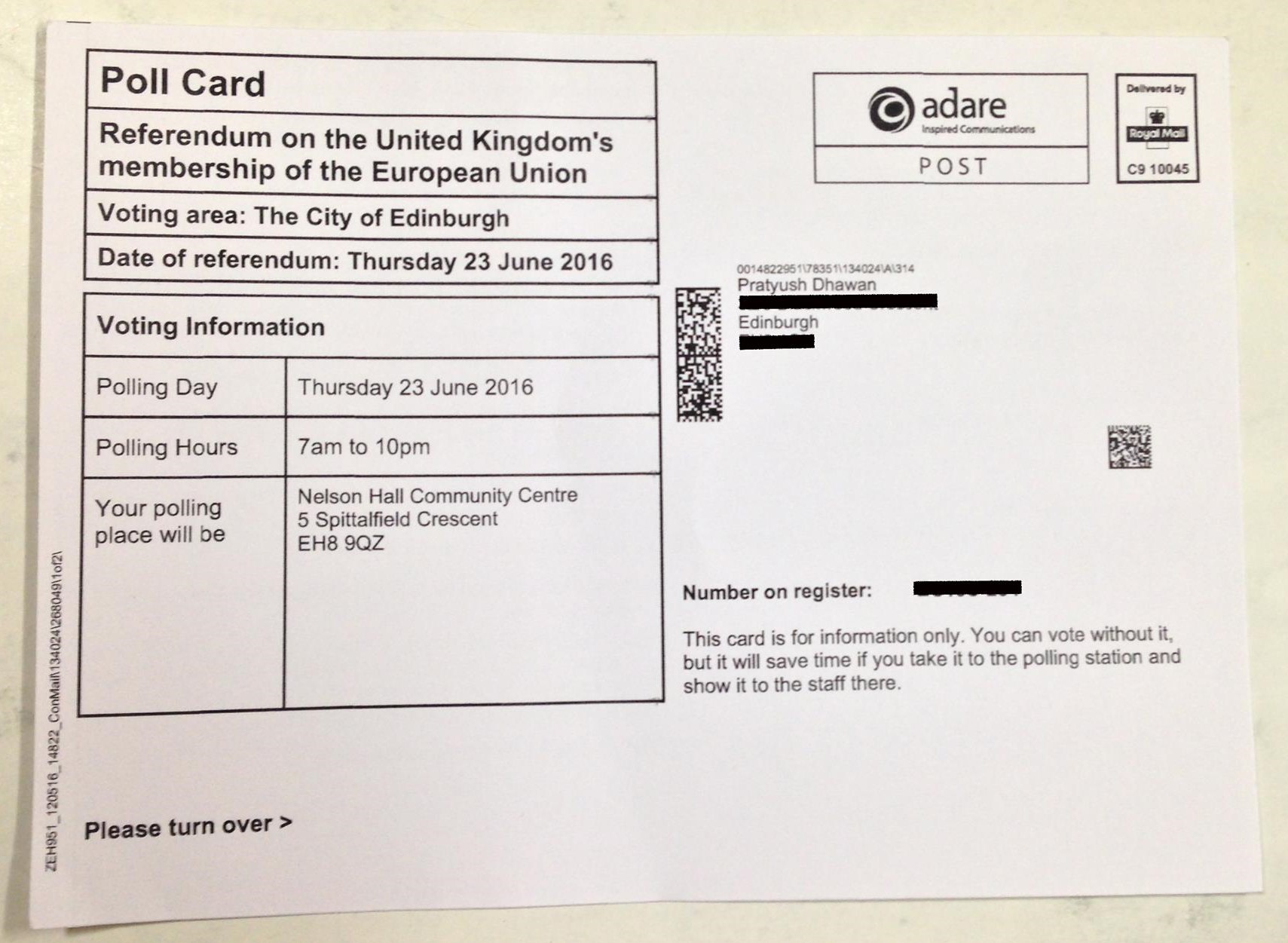

I cannot remember exactly when the poll card arrived. It could have been anywhere from a couple of months to a couple of weeks before the referendum’s date. Initially, I thought it was a mistake. I had largely ignored the noise of the Brexit vote, until it found its way through the mail slot. Something that was an occasional, distractive sideshow suddenly became a lot more important. My tone went from light-hearted nonchalance to invested beneficiary in debates – in classrooms, pubs, and online forums. Apparently, if you were a resident of Scotland, older than 16, and your head of state was the Queen, your voice mattered in this seismic yes-or-no contest. As a Canadian citizen, I got a card. My acquaintances, nationals of Asian and African colonies-turned-republics, received no such summons.

It was a summer of discontent in the UK. The Brexit referendum was an unsurprising announcement that nonetheless caught everyone off guard. Propaganda and misinformation were the norm, even on state-affiliated media. Unedited quotes filled headlines from the BBC to The Sun, as the hubris of those committed to the EU project went up against the supplications of those pleading for a permanent break from the establishment in Brussels. The former did not take the opposition seriously, while the latter were lost in delusion. Neither side knew what was coming.

As an outsider not quite distilling the nuances, I admit being compelled to either side of the debate from time to time. Though I realized that everyone voting either ‘Remain’ or ‘Leave’ seemed to be doing so for different reasons incongruous with their peers. The whole episode felt futile yet would in hindsight be one of the key case studies of an early 21st century world polarized by social media feedback loops and defined by discourse at the extremes; not a shifting of the Overton window but one operating at full stretch. In a tradition that is now mirrored in American politics, those on the far-right and far-left found themselves aligning on either side hoping for entirely different prospects. Radical change needs radical impetus. The referendum became a litmus test of how well a public can discern fantasy from reality, how well they could cope with a bombardment of nonsense. They did not fare well.

When June 23rd arrived, I made my way to the polling station, took the graphite pencil, and filled in the ‘Remain’ box. Like everyone else, I was just looking forward to the noise dying down. And like everyone else, I waited for the polls to close and for the results to come in. As the reports filtered through various news outlets, many across the kingdom had a sleepless night. Turnout was higher than in general elections; the public was galvanized. It was going to be a close call. Well into the night, many refreshed the webpages on their phones and laptops as they followed the live coverage county by county, as the dial shifted back and forth like a compass aboard a vessel navigating choppy waters. As the tide subsided and it settled on ‘Leave’, the notifications sounds pierced the din.

The UK, astoundingly, had voted to disassociate itself from the EU. Within a day, the Prime Minister would resign. The leader of the opposition, whose position on the referendum was at odds with his party’s, would find himself further and further away from power as the months and years wore on. The UK had confirmed itself as the site of an unwanted carnival that would not end until the Tories lost their pedestal. Given the political landscape, no one expected this to happen anytime soon. The country would begin its cycle through damaging figureheads with diminishing returns, culminating in an election eight years on that would restore only a semblance of normalcy to proceedings.

The next day, my friends and I made our way down to the Scottish parliament. Hundreds had gathered to protest a great injustice. The UK may have wanted to leave, but Scotland had voted to stay. Edinburgh, overwhelmingly so. Despite these demonstrations, nothing would change. The optimists reignited their dream of another ballot on Scottish Independence.

One fragment stands out from that day. Right across the road, a couple of apartment balconies had the Union Jack unfurled and on display, seemingly mocking those below in resolute defiance. This is democracy, kids. Deal with it.

– / – / –

Elections in the UK, and in so many other places these days, are akin to cricket. Just as athletes put on their uniforms and head out to battle each other on the pitch, politicians don their suits to verbally joust in halls of power. But in politics, as in that particular sport, we are in constrained coliseums. An old boys club that selects combatants from a paltry few. Those without money, privilege, and socio-economic connections that cannot be leveraged need not apply. The people who find themselves at the crease may be worthy; that is despite the selection process, not because of it.

The new PM has been selected from a small collection of old faces. His primary rival, Rishi Sunak, comes from a family reportedly wealthier than the King himself. Another, Nigel Farage, is somehow still on stage. The driving force behind the Brexit vote, which has led the UK to some of its most disastrous years. You could not make this stuff up.

The game itself becomes a dishonest exercise. The illusion of competition because so many have been excluded to create conditions that favor the status quo. The nobility, in both arenas, the ultimate barrier to true egalitarianism.

I did not know I would be writing about the election until I finished work today. No idea why certain thoughts come flooding in when they do. Anyway, here are some on-theme songs from our cousins across the Atlantic. A few British tunes to close out this rumination.

A ‘democratic monarchy’ is built on contradictions. “Unorthodox” captures many more for your enjoyment:

Forever being watched by Big Brother, in all his forms, a “Major Minus”:

Finally, “Galvanize”, often an anthem for troubled times: