Weekly Picks – February 16, 2025

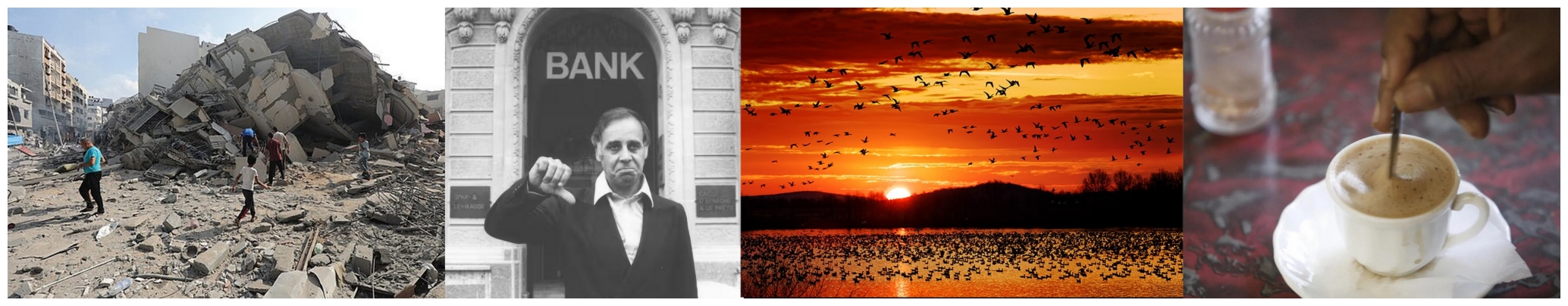

Credit (left to right): Palestinian News & Information Agency (Wafa) in contract with APAimage; ullstein bild Dtl. / ullstein bild / Getty Images; Delmas Lehman / Shutterstock; Jose Cendon / AFP via Getty Images

Credit (left to right): Palestinian News & Information Agency (Wafa) in contract with APAimage; ullstein bild Dtl. / ullstein bild / Getty Images; Delmas Lehman / Shutterstock; Jose Cendon / AFP via Getty Images

This week’s collection:

- A Brief History of Coffee and Colonialism | Foreign Policy

- The Prophet Business | The New York Review of Books

- ‘Here lives the monster’s brain’: the man who exposed Switzerland’s dirty secrets | The Guardian

- The Unnatural History of Bird Flu | Nautilus

- Proem: The Trauma of Gaza Scholasticide | Informed Comment

Introductory excerpts quoted below. For full text (and context) or video, please view the original piece.

1. A Brief History of Coffee and Colonialism

“Today, Brazil remains the dominant producer, 37 percent. And then next, it’s kind of fascinating—you might think Colombia, maybe Indonesia or Ethiopia, if you’re thinking history. But no, Vietnam is the second-largest global producer, accounting for 17 percent. Colombia and Indonesia 7 or 8 percent each. And Ethiopia, the original home of coffee, is only 4 percent. And that’s actually a big issue right now with the European Union because coffee is a small-scale peasant production in Ethiopia and the EU is imposing land-use rules that are a burden on them.

. . .

So the entire world economy is still, to a very considerable extent, a mirror of the colonial era, right? The richest countries in the world are themselves imperial players, and the poorest countries are the victims of colonial politics. And that’s a given. But it’s very striking. For some commodities, those effects have leveled out. So cellphones, for instance. You know, sub-Saharan Africa has very, very complete cellphone coverage now. Even though it’s home to, by far and away, the poorest people in the world and has not found the place in the global division of labor it needs. And in certain areas, in limited areas of technology, they are at the races. But in other respects, in terms of basic capital equipment, they are not. And also with regard to different types of consumption—like coffee consumption—not. And so this is where you really see the legacies of colonialism still inscribed.”

The article is only a brief excerpt of the entire discussion. You can listen to the full podcast here.

“There have always been futurologists of one kind or another, which already says something about humanity. In ancient times they were oracles, prophets, soothsayers, and astrologers. They discovered the future in entrails and tea leaves. No matter how often they were discredited, the need remained.

Our own futurologists predict election results and hurricanes. They augment imagination with science, which makes them respectable. They accept uncertainty and model probabilities. The pace of modern life makes their work lucrative and necessary. Every major corporation employs futurologists, whether they call them market researchers, trend analysts, or cool hunters. Science fiction writers are futurologists, too—often running ahead of the scientists. Which forecasters to trust, which to follow, is the special challenge of our time.

. . .

Leaving aside fortune tellers and charlatans, the business of prophecy had long belonged to religion, organized and otherwise. The first modern futurologists set themselves up as secular prophets, asserting a rational claim to truth. Since the future arrives piecemeal, they had to earn credibility. What first brought data-driven predictions into daily life was weather forecasting, a scientific innovation of the nineteenth century (messaging by telegraph was a prerequisite). Adamson notes that the basic conceptual breakthrough was a trick: “The future was contained within the present. That is, a lot of tomorrow’s weather is already here today; it’s just somewhere else, usually a little farther west.” Like all futurology, meteorology was, and is, notoriously error-prone, but even probabilistic weather forecasts had great value, so national governments, starting with Britain, established weather bureaus, and newspapers began printing forecasts. “Older vernacular methods—almanacs, moon observation, fingers held up to the wind—were rendered useless,” Adamson writes. “It must have seemed like magic.”

Where else could the magic be deployed?”

3. ‘Here lives the monster’s brain’: the man who exposed Switzerland’s dirty secrets

“In early 1964, Jean Ziegler, a young Swiss politician, received a phone call from a man claiming to represent Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Cuban revolutionary and minister of industry. Che would be in Geneva in March for a UN conference on trade policy, and some comrades had suggested Jean might be his chauffeur during his stay. Was Ziegler available for the gig?

Today, in his tenth decade of life, Ziegler is Switzerland’s most notorious public intellectual. That’s because, over the course of writing about 30 books, serving for close to three decades in the Swiss parliament, and relentlessly crusading for leftwing causes in his free time, Ziegler has made a career of unsparing criticism of his home country and its outsize influence on the rest of the world. In the 1960s, though, he was just another eager young leftist, waiting for his chance to change the world.

Ziegler, like Che, was born into a family of upper-middle-class professionals. And, like Che’s, his travels around the world had radicalised him against what he perceived to be a capitalist, imperialist and racist system. Everywhere he went, he saw its ravages: in the Belgian Congo, whose hungry children haunted him long after he went home; in Algeria’s bloody wars of independence against the colonial French; and in annexed Cyprus, where the British had deprived citizens of their right to self-determination for decades.

Ziegler heard the echoes of oppression closer to home, too, in the deracinated commodity exchanges through which speculators bet on the price of food and fuel; and in the bank vaults mere steps from his home, where kleptocrats siphoned away their countries’ natural resources.

For centuries, the Swiss had prided themselves on keeping blood and money apart: of keeping its bank vaults isolated from the upheavals of the outside world. In Ziegler, they spawned an iconoclastic figure who forced them to reckon with the moral cost.”

4. The Unnatural History of Bird Flu

“Since the COVID-19 pandemic, few scientific questions have received as much public attention as the origin of the deadly virus: people or nature. It was the subject of journalists’ investigations and government hearings and academic recrimination; it became part of the culture war. It is perhaps strange, then, that little attention is paid to the role people have played in another potential pandemic virus: H5N1 avian influenza, a creation of modern poultry production systems.

The earliest forms of H5N1 were identified nearly three decades ago in Guangdong, China, a region rapidly adopting the industrial husbandry practices common to North America and western Europe. A subsequent outbreak in Hong Kong infected 18 people, six of whom died; the virus did not transmit easily between humans and was soon contained, but H5N1 was not extinguished. Since then, it has spread around the planet, leaving mountains of chicken carcasses in its wake, and also silent seabird colonies and beaches covered with dead seals. H5N1 has killed 464 people so far—not a large number, but the possibility of it becoming better at infecting humans is ever-present. The historical precedents are grim.

The first modern influenza pandemic, in 1918, killed an estimated 50 million people. Several million people died in the pandemics of 1957 and 1968, and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic killed about 350,000 people in its first year. During the latter pandemic, the virologist Yi Guan—renowned for helping contain the 2003 SARS outbreak—said that if H1N1 and H5N1 mixed, he would “retire immediately and lock myself” in a high-security lab for protection. And as the Covid pandemic showed, even a disease with relatively low mortality rates can be cataclysmic.

. . .

In June 2024, a total of three H5N1 infections had been reported in the United States; seven months later, that number stood at 67. Although symptoms remain mild, and the virus still does not transmit easily between us, scientists are spooked. Those I talked to for this story used phrases like “red lights flashing,” “totally novel ballgame,” “no hope of containing,” and “under attack.”

Media coverage of H5N1 captures this urgency but tends to focus on the day-by-day—the latest “depopulation,” as mass exterminations at poultry facilities are known, the latest sick cows or dead cats, the latest mutations. Lost in the furor is a clear sense of where H5N1, and the class of influenzas to which it belongs, comes from: the evolutionary crucible of intensive animal production.

In the facilities—the artificial ecosystems—that now house much of Earth’s terrestrial vertebrate biomass, constraints on virulence that prevail in natural ecosystems are not merely removed. Virulence is actually favored. In the words of Mark Woolhouse, an epidemiologist at the University of Edinburgh, the viruses are “a response to the selection pressures that exist in a human creation: the modern poultry farm.””

5. Proem: The Trauma of Gaza Scholasticide

“What are the consequences of buildings saturated with grime and rubble and the ache of children emerging from debris and tents made desolate with cries that fill the void?”

One of many stories linked here.