Weekly Picks – February 23, 2025

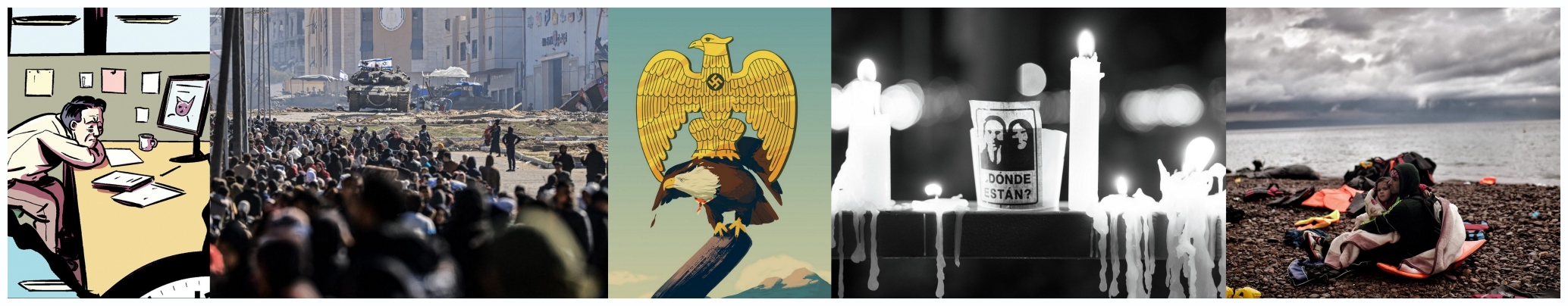

Credit (left to right): Current Affairs; Mahmud Hams / AFP via Getty Images; Fabio Consoli; Kitra Cahana; Aris Messinis / AFP via Getty Images

Credit (left to right): Current Affairs; Mahmud Hams / AFP via Getty Images; Fabio Consoli; Kitra Cahana; Aris Messinis / AFP via Getty Images

This week’s collection:

- The Reality of Settler Colonialism | Boston Review

- The Fourth Wall | In These Times

- Grave Mistakes: The History and Future of Chile’s ‘Disappeared’ | Undark Magazine

- Did you think you were safe? | Aeon Magazine

- Why Japan Succeeds Despite Stagnation | Uncharted Territories

- The Fork in the Road | n+1

- Kings of Capital | In These Times

- The Shrouded, Sinister History of the Bulldozer | Noema Magazine

Introductory excerpts quoted below. For full text (and context) or video, please view the original piece.

Plus, an essay from last year that I was only able to fully read recently (quite appropriately, while on an eighty-minute transit journey to the office):

- The Problem With Work | Current Affairs

Finally, some unique angles on our world:

- Winners of the 2025 World Nature Photography Awards | The Atlantic

1. The Reality of Settler Colonialism

“Settler colonialism falls into the category of concepts that may provoke guilt in a certain type of liberal and fury in a certain type of conservative. For liberal nationalists, including liberal Zionists like Kirsch, the typical response is something in between: a defensive fragility. Like “gender performativity” and “critical race theory,” “settler colonialism” was until fairly recently the province of a relatively small academic field, though it has now broken containment and entered the world of public discourse (losing something in translation, as such breakthroughs always do). The basic idea of settler colonialism is that in addition to classic colonialism, in which a wealthy and powerful country establishes military and economic control over a weaker one to extract its resources, there is also another type, in which settlers arrive with the goal of taking over the land completely, evicting, displacing, or eliminating the native peoples. Paradigmatic examples of the former are France in Indochina and Britain in India; paradigmatic examples of the latter are the United States, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

If this seems reasonable or uncontroversial to you, well, that’s why the field of settler colonial studies wasn’t immediately a lightning rod from the moment of its founding in the 1990s. Arguments over the taxonomy of colonialism according to regime type and political economy can be dry stuff. The ideas of settler colonial studies have been slowly taken up in varying degrees by other fields, from history and anthropology to Indigenous studies, but what makes it a hot topic now is the highly visible public inclusion of another country in the category: the State of Israel.”

“The boat, like all boats that contact the Aegean Boat Report — the official name for this one-man hallway operation thousands of miles from the Aegean — was on its way to Greece from the shores of Turkey, crossing the treacherous gateway into the European Union in pursuit of protection.

The group sent Olsen their coordinates and a video of the boat charging forth into the full, bright light of the Greek summer. It was an inflatable vessel with 31 people crammed inside, all from West Africa. He’d seen far worse — sometimes boats like this carry 50, lining smugglers’ pockets with more cash at the expense of the refugees’ safety — but even so, this boat was unsteady. The men sat perched on the pontoons with the women and children nestled at their feet.

Then the video took a sinister turn.

A Coast Guard boat was fast approaching. While this might have first appeared to be a rescue operation, it quickly became clear it was what’s commonly called a pushback, an illegal practice of forcibly returning refugees from whence they came.

The Coast Guard vessel was menacing with a machine gun mounted at the bow. Then a fiberglass speedboat came into view, also mounted with a gun. The camera bobbled in the chop as the passengers panicked; they yelled to the Coast Guard officers for help and shrieked in distress as their boat keeled and lurched.

“Please,” they implored the authorities in English. “Please!” The refugees were most likely filming because, like many refugees arriving to Greece, they knew all about pushbacks, reports of which had become commonplace. Greek authorities have been routinely and credibly accused of attempting to stop refugees from arriving on EU soil by hauling their boats back to Turkish seas, and even rounding up refugees once they’d made landfall in Greece.

Refugees crossing this stretch often held up a camera in hopes to stop a pushback, in part by sharing the footage with the Aegean Boat Report.

That was 2021. In previous years, pushbacks had become Tommy Olsen’s obsession, something he juggled alongside his day job. If he kept documenting them, he thought, perhaps he could stop them.

Olsen watched as the authorities escorted the boat toward shore before bringing the flotilla to a halt. The group of refugees grew quiet. But then the authorities on the Hellenic Coast Guard vessel began to mount the gunwales, boat hooks in hand. One officer, face shrouded in a balaclava, emerged from the hardtop with a machine gun pointing skyward. At that, the refugees began to panic again. According to hundreds of witness testimonies collected by human rights organizations over the years, it wasn’t uncommon for authorities to point guns directly at the passengers and use boat hooks and other tools to pierce the pontoons or smash the engines.

One of the refugees pointed out a pregnant woman in the boat. “We will die with a baby! And you’ll be happy!”

Over the next 10 minutes, the situation grew even more tense. It was unclear what the Greek authorities were planning. Eventually, the refugees began shouting at the officers; in response, one officer slapped his hands over his crotch, the international signal for “suck it.”

There’s really nothing Olsen could reliably do to stop this or any pushback. Sometimes, especially when people manage to make it to shore and tell him they are hiding in the nearby woods to avoid detection, he alerts the Greek authorities and human rights agencies in hopes that making an official record will make it less likely the refugees will be disappeared. At the time this particular video was taken, more often than not, the refugees who contacted him ended up spirited away.

This is, in part, because Greek authorities had effectively outlawed volunteers, NGO workers and even journalists from coming to refugees’ assistance. Anyone found at a boat landing risks arrest. That means there are fewer people assisting refugees upon first arrival (in contrast with just a few years ago, when Greek beaches would sometimes be packed with more eager-to-help volunteers than refugees on boats). It also means there are few witnesses.”

3. Grave Mistakes: The History and Future of Chile’s ‘Disappeared’

“In August of 2023, as the 50th anniversary of Augusto Pinochet’s bloody 1973 coup d’état drew near, President Gabriel Boric of Chile stood before the presidential palace in downtown Santiago and spoke about memory. “During these days in which there are people who dare to deny all of this,” he said in Spanish, referring to the country’s rising denialism of Pinochet’s spate of crimes, “how do you respond to those people who invite us to forget?”

The question wasn’t merely rhetorical. Beneath a wide canopy blocking the midday sun, a few hundred people — relatives of Pinochet’s victims, journalists, a coterie of government officials — had gathered to hear Boric unveil his administration’s response: The Plan Nacional de Búsqueda, or National Search Plan, a highly anticipated initiative harnessing new technologies and scientific techniques to uncover the remains of Chileans abducted and likely killed as part of Pinochet’s infamous, post-coup crackdown. More than 1,000 victims of such enforced disappearance have never been found. Of those who disappeared, Boric said, “we want to recover their stories to be able to reconstruct our own, because when we forget, we also lose a fragment of ourselves, of what we can be.”

“My memory,” he added, “is incomplete because I am missing the disappeared.”

The oratory was effective — tears flowed freely, and the occasional cry of “Que Viva Presidente Boric!” issued from the crowd. But for Flor Lazo, the president of the Association of Relatives of the Detained, Disappeared, and Executed of Paine, memory had never been a problem. Her father, two brothers, and two uncles had been among the 70 people who were forcibly disappeared from Paine, a small agricultural area 30 miles south of Santiago, in the weeks following the coup — the worst per-capita case of repression of the entire dictatorship. For decades, Lazo, like so many others, had searched for her loved ones. For her efforts, she had suffered maltreatment, indifference, and humiliating scientific blunders by the state, the last occurring after Pinochet’s reign had ended. As she sat in the front row listening, the betrayals cast a shadow over Boric’s lofty rhetoric. “Trust,” she had explained a few weeks prior, “is something that is very delicate.””

A supplemental documentary that may be of interest to those who appreciated this dive into recent Chilean history: Nostalgia for the Light.

4. Did you think you were safe?

“As women in India make tentative strides towards greater liberty and individual rights, their progress has not been taken kindly by all sectors of a staunchly patriarchal, misogynistic society. Living in Bengaluru amid the changing winds and careless promises of the early Modi era, it was easy to forget that this was still a country ranked 130th out of 155 in the United Nations’ Gender Inequality Index (2015), and where, according to the UN Population Fund (2020), almost half a million baby girls went ‘missing’ every year through sex-selective abortions and infanticide. The average age of marriage for women hovered around 19, and, despite the gains made in education, the International Labor Organization (2014) estimated that only a quarter of adult women participate in the labour force – among the lowest rates in the world. While upper-class women have ascended to the C-suite, even the office of prime minister, male supremacy remains the status quo.

As India’s riches have grown over the past decade, they have coincided with historic levels of inequality, with the top 1 per cent accruing 40 per cent of the country’s wealth, while the bottom half continues to survive on less than $3 a day. Hundreds of millions of men continue to find themselves in a poverty trap, increasingly left behind by India’s generational growth story and, as their grip on entitlement start to waver, they feel even more threatened. It is easy to imagine how, when confronted with women’s onward march toward greater independence, men resort to violence to put women in their place and reassert their own power. If they control nothing else, they can control women’s bodies; and any female is a target – from infants to elderly widows, in public spaces, in the home.

There is a grievous lack of sex education in India, driven by conservative attitudes that regard any discussion of sex as taboo, while several populous states have banned sex education outright. The researcher Madhumita Pandey and the journalist Tara Kaushal, who each spoke to rape convicts in the aftermath of Nirbhaya, affirmed that none of their subjects had received sex education or understood the concept of consent; in many cases, they even failed to understand the crime they were being charged for. In this vacuum, many young men learn about sex through pornography and Bollywood movies that glorify men who stalk and aggressively pursue their romantic interests until they relent. While the global discourse around Nirbhaya condemned the country’s ‘rape epidemic’ and framed the rapists as ‘monsters’, inside the country itself there was an equally potent narrative that blamed the victim. One of the accused, sentenced to the death penalty, openly said that they had wanted to teach the female college student a lesson for staying out after hours with a male acquaintance.

. . .

To me, it was a relentless cycle of violation and retreat, followed by advances that met with further violation. Social change is slow: women have to buy time until, one day, the values of equality and respect sufficiently penetrate the majority, and the guardrails can come off. But how can this happen when ‘those people’ continue to be othered and shut out of systemic reform?”

5. Why Japan Succeeds Despite Stagnation

“For more than three decades, Japan has endured near complete economic stagnation. Since 2000, Japan’s total output has grown by only $200B.

That’s less additional output than Nigeria, Pakistan, and Chile, even though they all started from much lower bases, and only around a fifth of South Korea’s growth over the same period.

But despite severe economic stagnation, Japan is still a desirable place to live and work. The major costs of living, like housing, energy, and transportation are not particularly expensive compared to other highly-developed countries. Infrastructure in Japan is clean, functional, and regularly expanded. There is very little crime or disorder, and almost zero open drug use or homelessness. Compared to a peer country like Britain, whose economic stagnation over the past 30 years has been less severe, Japan seems to enjoy a higher quality of life.

What explains Japan’s lost decades? And how has the country still managed to maintain such a high quality of life?”

“In historical terms, the event we are witnessing is an attempt at Gleichschaltung. The Nazi term is usually translated “coordination,” sometimes “consolidation” or “streamlining.” In this phase of totalitarianism, the Movement, now elected to power, uses its hold on the legitimate authority of the state to try, illegitimately, to align neutral, nonpartisan, or independent institutions with the extra-state Movement, forging an obligation to the Leader rather than to the constitutional state.

The hallmark of totalitarianism at this stage isn’t genocide or extremes of violence. It is doubled or twofold organization. The Movement (here MAGA) or its party (here the Republican Party, parasitically devoured and replaced from within) generates a vision of second institutions, however hallucinatory or inverted, with which original or real institutions are then coordinated.

The task of coordination is to reshape, refound, purge, and, by all means foul and fair, shake the underlying basis of institutions and install new, arbitrary ones. Because institutions only subsist by their personnel, a Gleichschaltung should unnerve the committed participants in institutions, first within government and then in civil society, and mold minds toward constant doubt and adjustment. Personnel should feel that they require alignment with the leader, or acknowledgment of arbitrary or irrelevant Movement goals, simply to continue to work and to avoid baseless investigation or denunciation.

. . .

In the midst of it all, on TV news, or in the ambient online sphere of images of “what is going on in America,” were the roundups of immigrants, ICE agents dressed up as commandos heading into poultry farms, construction sites, car washes; deportation flights; lines of shackled or zip-tied men and women, heads down in shame or exhaustion; publicity for orders to pursue migrants into hospitals, churches, and schools; and a tent city going up at Guantanamo, last cradled in the American mind as a place to hold and torture 9/11 terrorists. It is hard to measure the transfer of anticipatory fear from one population to another. But it would need a very stony-hearted citizenry to witness this without alarm and dread.

Simple advice can be offered to anyone in a decision-making role at an institution. Every tub must stand on its own bottom. If you can find solidarity with other institutions like your own, do it. But even when you can’t prevent others from defecting, there need be no solidarity in weakness. Prepare to stand on your own for a bit. Reach into reserves if they exist. Delay programs if you must. Don’t change, or kneel, or find hostages to feed into a slobbering maw. Don’t coordinate yourself, don’t align yourself, don’t appease, when it may yet prove unnecessary.

There may well be normalcy again. But it lies on the other side—not in accommodation to this malevolent insanity, run by lackeys and toads. The risk of overreaction is trivial compared to the risks of accommodation.”

The author of this piece, Mark Greif, also wrote one of my favorite essays of this century, on those tasked with law enforcement: Seeing Through Police. For those into uncompromisingly human analysis.

“Across right-wing culture, we witness an angry reassertion of masculinity that cuts across and connects the domestic and the national.

But we are not dealing with mere reactionary nostalgia. These patriarchal fantasies reflect concrete political and economic transformations that any progressive challenge to authoritarianism must confront. One is the erosion of any degree of public control over capital and markets. The other is the unchecked growth of a national security state in which executive power rules by decree, bypasses the legislative branch and repeatedly suspends civil liberties.

Within this order, the rule of finance and the rule of force are almost invariably embodied in belligerent and narcissistic forms of masculinity: powerful men who claim unique abilities to lift the nation out of a crisis — i.e., Trump’s “American carnage” — that is presented as simultaneously affecting gender, culture, the economy and the state.

Do we have the vocabulary to name and analyze this kind of power, which respects no boundaries between the political and the economic? Do we risk being mesmerized by the lucre and the trolling, distracting us from the deeper social realities that have given rise to these capitalist autocrats? Beyond the horror and ridicule, what is to be done with these supersized 21st-century sovereigns? And how are we to gauge the social and geopolitical effects of a form of power that originates not in impersonal market mechanisms or state bureaucracies, but the whims of a very few men?”

8. The Shrouded, Sinister History of the Bulldozer

“If, like gods, we aspire to create machines in our own image, then it’s fitting that the original bulldozers were humans. Leading up to the corrupted U.S. election of 1876, as the Southern states were being reconstructed following the Civil War, terrorist gangs of predominantly white Democrats roamed about, threatening or attacking Black men who they thought might vote for the Republican Party. The thugs were the bulldozers, and the acts they carried out were bulldozing.

Wearing black masks or black face paint, and, on occasion, goggles, they brutally whipped, beat and sometimes murdered their victims. In June of that year, a Louisiana newspaper reported that bulldozers took a Black Republican voter named W. Y. Payne from his bed in the night and hung him from a tree two miles away. Later that month, in nearby Port Hudson, a Black preacher named Reverend Minor Holmes was hung from the wooden beams in a Baptist church by bulldozers, but they cut him down before he died.

“The good people have been cowed down, brow-beaten, insidiously threatened, forced to silence or worse, the countenancing of outrages, blackmailed and their contributions made the lever for future extortions, their tongues muzzled, their hands tied, their steps dogged, their business jeopardized and themselves living in continual fear of offending the ‘bulldozers,’” read an article in the New Orleans Republican in June. By the following year, the association of “bulldozer” with rampant voter suppression during the election made it a common term across the U.S. for any use of brutal force to intimidate or coerce a person into doing what the aggressor desired.

It’s hard to trace when the word first became a label for machines. For decades, it floated around the language tree, resting a while on branches where some instance of terrific violence needed a novel and evocative label. A handful of arms manufacturers marketed various “bulldozer” and “bulldog” pistols in these years. As the 19th century came to a close, it popped up in a Kentucky newspaper as a term for a towboat used to smash through heavy ice and in an Illinois court case to describe a manufacturing machine that had ripped off a worker’s left arm.

The bulldozer we know today took shape in the first quarter of the 20th century. In 1917, the Russell Grader Manufacturing Company advertised a bulldozer in their catalog: a huge metal blade pulled by mules that could cut into the earth and flatten the land. Other manufacturers like Holt, Caterpillar and R. G. LeTourneau were working on similar devices, technological descendants of scraping tools developed in the American West and associated with Mormon farmers. In time, animals were replaced with tractors (on either wheels or continuous tracks) powered first by steam, then gasoline and eventually diesel. The word, which at first referred only to the blade itself, started to mean the entire machine, one that was unrivaled in its ability to rip, shift and level earth.

. . .

It’s not commonplace to associate bulldozers with war, and yet they were as important to the Allied victory as the jet engine, the radar or the atomic bomb. “Of all the weapons of war,” wrote Colonel K. S. Andersson of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1944, “the bulldozer stands first. Airplanes and tanks may be more romantic, appeal more to the public imagination, but the Army’s advance depends on the unromantic, unsung hero who drives the ‘cat.’” The war was largely defined by control of the air, and airplanes needed airfields within operating range of their targets. If dispatched from seafaring aircraft carriers, then those ships needed docks and dry docks. And those airfields, docks and dry docks needed bases and road systems. In essence, for airplanes to stay mobile as the front shifted across the planet, an entire network of ordinarily immobile infrastructure had to become mobile too. Bulldozers move wars.”