Weekly Picks – March 23, 2025

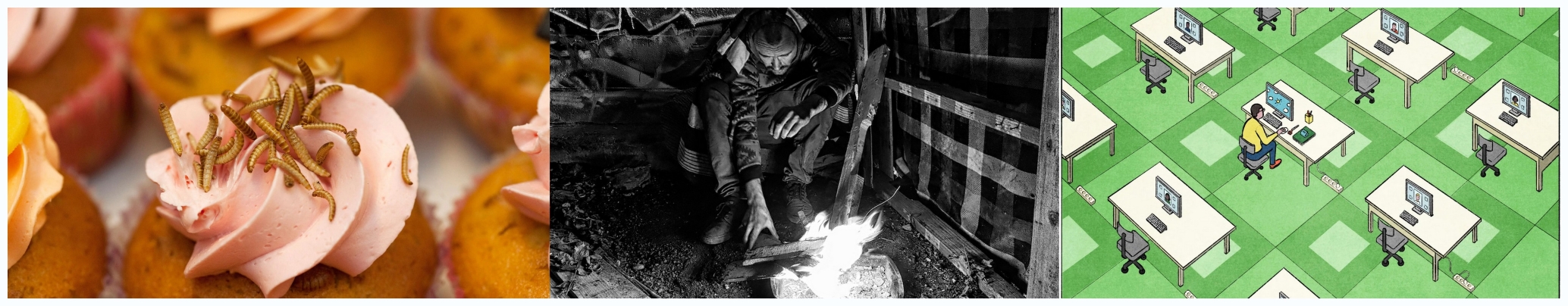

Credit (left to right): Michael Kooren/ Reuters; J. M. Simpson/ Jacobin; David Plunkert

Credit (left to right): Michael Kooren/ Reuters; J. M. Simpson/ Jacobin; David Plunkert

This week’s collection:

- The internet that could have been was ruined by billionaires | The Real News

- The Violence Prerogative | The Boston Review

- War Architects Enjoy Top Academic Gigs 22 Years After Illegal Invasion of Iraq | Truthout

- An Autonomy Worth Having | Jacobin

- Going Soft | Harper’s Magazine

- Adjust your disgust | Aeon

- What’s the Matter with Abundance? | The Baffler

Find out how these weekly lists are compiled at The Explainer.

Introductory excerpts quoted below. For full text (and context) or video, please view the original piece.

1. The internet that could have been was ruined by billionaires | Maximillian Alvarez interviews Cory Doctorow

A great conversation all round. Aside from the internet’s makeup in a capitalist world, Doctorow touches on many more topics, including the role of genre fiction, intellectual property, international trade, and modern political movements. As of the time of writing, the transcript is a little incomplete; I would suggest listening to the podcast in its entirety (length: 43min).

2. The Violence Prerogative | Noam Chomsky & Nathan J. Robinson

“Every ruling power tells itself stories to justify its rule. Nobody is the villain in their own history. Professed good intentions and humane principles are a constant. Even Heinrich Himmler, in describing the extermination of the Jews, claimed that the Nazis only “carried out this most difficult task for the love of our people” and thereby “suffered no defect within us, in our soul, or in our character.” Hitler himself said that in occupying Czechoslovakia, he was only trying to “further the peace and social welfare of all” by eliminating ethnic conflicts and letting everyone live in harmony under civilized Germany’s benevolent tutelage. The worst of history’s criminals have often proclaimed themselves to be among humankind’s greatest heroes.

Murderous imperial conquests are consistently characterized as civilizing missions, conducted out of concern for the interests of the indigenous population. During Japan’s invasion of China in the 1930s, even as Japanese forces were carrying out the Nanjing Massacre, Japanese leaders were claiming they were on a mission to create an “earthly paradise” for the people of China and to protect them from Chinese “bandits” (i.e., those resisting Japan’s invasion). Emperor Hirohito, in his 1945 surrender address, insisted that “we declared war on America and Britain out of our sincere desire to ensure Japan’s self-preservation and the stabilization of East Asia, it being far from our thought either to infringe upon the sovereignty of other nations or to embark upon territorial aggrandizement.” As the late Palestinian American scholar Edward Said noted, there is always a class of people ready to produce specious intellectual arguments in defense of domination: “Every single empire in its official discourse has said that it is not like all the others, that its circumstances are special, that it has a mission to enlighten, civilize, bring order and democracy, and that it uses force only as a last resort.”

Virtually any act of mass murder or criminal aggression can be rationalized by appeals to high moral principle. Maximilien Robespierre justified the French Reign of Terror in 1794 by claiming that “terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible; it is therefore an emanation of virtue.” Those in power generally present themselves as altruistic, disinterested, and generous. The late leftist journalist Andrew Kopkind pointed to “the universal desire of statesmen to make their most monstrous missions seem like acts of mercy.” It is hard to take actions one believes to be actively immoral, so people have to convince themselves that what they’re doing is right, that their violence is justified. When anyone wields power over someone else (whether a colonist, a dictator, a bureaucrat, a spouse, or a boss), they need an ideology, and that ideology usually comes down to the belief that their domination is for the good of the dominated.

. . .

Needless to say, because even oppressive, criminal, and genocidal governments cloak their atrocities in the language of virtue, none of this rhetoric should be taken seriously. There is no reason to expect Americans to be uniquely immune to self-delusion. If those who commit evil and those who do good always both profess to be doing good, national stories are worthless as tests of truth. Sensible people pay scant attention to declarations of noble intent by leaders, because they are a universal. What matters is the historical record.”

3. War Architects Enjoy Top Academic Gigs 22 Years After Illegal Invasion of Iraq | Derek Seidman

“Today, on the 22nd anniversary of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, key architects and commanders of this monstrous war crime, from Condoleezza Rice to David Petraeus, sit comfortably in cushy positions at top American universities.

At the same time, the overseers of the ongoing U.S.-backed Israeli bombardment and siege on Gaza, considered a genocide by human rights groups like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, are already settling into equally fancy appointments at elite schools. Just recently, Biden administration officials Brett McGurk and Jake Sullivan accepted gigs at Harvard, with Sullivan’s professorship named after none other than former Secretary of State and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger. Both Sullivan and McGurk were key officials who implemented Biden’s Gaza policies, and McGurk’s work stretches back to the Iraq occupation.

Many of these universities — Harvard to Yale, Columbia to Stanford — have made statements around injustices such as Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, but have mostly stayed quiet around Israel’s destruction of Gaza and scholasticide against Palestinian universities. These administrations have also aggressively repressed students who protested ongoing atrocities against Palestinians and demanded that universities break ties with Israel’s U.S.-backed war machine that oversees occupation and apartheid. The university response to dissent around the U.S.-Israel war on Palestine has been far more iron-fisted than anything seen during the Iraq War.

. . .

Brown University’s Costs of War project estimates that 315,000 Iraqis, overwhelmingly civilians, may have died during the invasion and occupation, though this is likely an undercount. Around 9.2 million Iraqis — 37 percent of Iraq’s prewar population — may have been displaced. All this came after years of devastating sanctions, some of which were implemented as early as 1990, one year before the first U.S. invasion of Iraq.

The U.S. occupation oversaw torture and massacres of Iraqis and led to massive sectarian violence and a ravaging of the nation’s educational system and public health. The war and occupation upended the region politically, leading to hundreds of thousands of more deaths and millions more displacements.

And yet, key architects and overseers of the second U.S. war on Iraq have been rewarded with prestigious teaching appointments and lucrative speaking gigs at U.S. universities.”

4. An Autonomy Worth Having | Paul Schofield

“We find ourselves in the midst of a homelessness crisis that has many revisiting the idea of involuntary hospitalization. Pointing specifically to the prevalence of mental illness and addiction among the chronically unhoused, politicians from California governor Gavin Newsom to New York mayor Eric Adams to President Donald Trump have advocated for legal reforms making it easier to forcibly institutionalize people.

Unsurprisingly, traditionally left-leaning advocates for the homeless have bristled at the suggestion. For instance, the American Bar Association recently adopted a resolution declaring “involuntary commitment is an infringement on [rights], involving the loss of liberty and autonomy,” while the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty urges the government to “respect autonomy and self-governance for [homeless] encampment residents.” Interestingly — and perhaps tellingly — the libertarian right has adopted this rhetoric as well. Jeffrey Singer, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, writes that “the government coercing people, directly or indirectly, to undergo mental health or drug addiction treatment flagrantly assaults their autonomy.”

Both views, however, rest on a fetishization of individual choice and overly dogmatic aversion to coercion. Rather than opposing any and all coercion, we should recognize the necessity — in many cases, at least — of affirmative measures that loosen the grip that mental illness, substance dependency, and economic deprivation have on so many people who live on the streets. That means advocating for a deeper autonomy, a kind of autonomy worth having.”

5. Going Soft | Lily Scherlis

““The world is facing a ‘soft-skills crisis’ as home working leaves millions of workers struggling to interact with colleagues,” the Telegraph of London reported. This “crisis” seems to be everywhere at once, now that soft skills are MORE IN DEMAND THAN EVER, as one Forbes headline put it; management scientists worry about “the discrepancy between employer demand and workforce supply of soft skills,” making the charm shortage sound like an urgent supply-chain disruption. The reports read as if executives might wander into the growing “skill gap” and fall to their deaths.

News coverage suggests that workers everywhere have yet to recover from the isolating effects of the pandemic. Socializing, we are told, is a matter of fitness. “Utilizing those skills is almost like a muscle. If you’re not using that muscle, it can become weak,” the founder of the Swann School of Protocol, a corporate-etiquette school, told the Los Angeles Times. “The COVID-19 pandemic has quickly and dramatically accelerated the need for new workforce skills,” the firm McKinsey & Company claimed in its Global Survey on Reskilling. “The most important skills to develop tend to be social and emotional in nature.” Now that pandemic-era college students have entered the workforce, the problem has only intensified. The accounting and consulting firm KPMG is trying to rehabilitate “lockdown-damaged” Gen Z recruits, wrote the Telegraph, as if Zoom had denatured their brains. Unfortunately, the soft-skills crisis might be part of a bigger problem: the so-called loneliness epidemic, or what The Atlantic has called “the anti-social century,” has driven people to the lowest recorded levels of in-person socializing in our country’s history.

. . .

When I mention soft skills to the occasional corporate leaders I meet through my research, they look grave. They tell me how crucial soft skills are and how hard it is to find them in job candidates, as though they were an elusive species of bird being hunted to death. Yet when I ask what they are or how they’re measured, no one can quite tell me. Researchers note that it’s hard to slot soft skills alongside the more rigorous conceptions we have of “skill”—a category once used to rank industrial workers on the basis of what kinds of machines they knew how to use. When I do encounter real social grace, it doesn’t seem like a matter of technical mastery, inherited privilege, or even virtuosity. It instead feels like a rare gift of real responsiveness—it offers a tiny glimpse of the sublime experience of brushing up against another person’s subjectivity.

. . .

But no matter how little quantitative evidence we have that soft-skills training helps employees, employers still preach soft skills as the key to individual success. If you’re emotionally dysregulated, if your boss resents you, or if you lose your job, it’s your fault for being unskilled.

Our current soft-skills panic, however, is not merely a vintage tactic of oppression from the Seventies, but also a folk remedy for distinctly contemporary social problems. While often described as an aftereffect of the pandemic, the “crisis” is also forward-looking, aided by McKinsey’s claim that soft skills will make businesses “future-proof,” as if sealing them against the biblical floods to come.”

6. Adjust your disgust | Alexandra Plakias

“Something in contemporary Western diets must shift, for both moral and ecological reasons. Fortunately, there are alternatives to our current food system – ways of eating that are equally, if not more, nutritious but without the suffering and climate impacts of factory-farmed meat. Unfortunately, many people find these alternatives disgusting.

I know, because I’ve been one of those people. My interest in disgust began almost two decades ago in graduate school, when I encountered an article describing scientists’ attempts to grow meat without animals. ‘In vitro meat’, now known as ‘cultivated meat’ or ‘lab-grown meat’, involves cultivating muscle tissue in bioreactors, using growth media and scaffolding to create threads of muscle that could then be massed together into hamburger patties or even a steak.

The idea of growing muscle tissue in labs for human consumption, independently of an animal body, seemed unnatural and repellent. It seemed, in a word, disgusting. But faced with more humane, sustainable options, is disgust a good enough reason to reject them? Is it any kind of reason at all?

. . .

The catalogue of things that disgust us is vast, but the core class of disgust elicitors involves bodily fluids (faeces and urine; pus, vomit, saliva, and snot) and exposed viscera. If it’s unclear what this has to do with food, well, that’s the point. Disgust originates in a fundamental problem: to survive, we have to eat, but eating can kill us. That’s because food is potentially contaminated by invisible pathogens and poisons, so it’s not enough to avoid eating faeces or vomit – one must avoid eating anything that comes into contact with faeces.

Taste solves part of this problem: our aversion to bitter and attraction to sweet tracks (albeit imperfectly) toxins, which tend to be bitter. But rejecting poisons is only half the battle. Pathogens and parasites can lurk, undetectable, in almost any food. Enter disgust.

. . .

Taste isn’t just personal – what people like is heavily influenced by culture. For example, American and European eaters tend to associate slimy textures with spoilage and find slimy foods disgusting; in Japan, the term ‘neba-neba’ refers to slimy, gooey foods like natto (fermented soybeans) that are full of insoluble fibre and (apparently) exceptionally healthy.

There’s an evolutionary explanation for this: familiarity indicates safety; at a time when any new food could be dangerous, strange smells, textures and flavours are best avoided. But if disgust is merely a proxy for difference, it’s not a reliable guide to danger in today’s food system. It can even deter us from eating otherwise nutritious or sustainable foods such as cultivated meat or insects.”

7. What’s the Matter with Abundance? | Malcolm Harris

“To maintain an interest in production means investigating the conditions and relations of production—not just the policy mechanics. A turn-of-the-century New Yorker might be thrilled with his new rubber goods and the innovation embodied therein. But we can’t forget the enslaved rubber workers of the Belgian Congo from whom the industry tortured its material. Life did not simply get better and easier with innovation, not even for white people: the violence of the imperial scramble rebounded on the European Metropole and the continent’s scientists turned their attention from fun new electronic doohickeys to killing machines.

If a hammer thinks every problem is a nail then Abundance must be the work of a plumbing snake. Whether housing, electric vehicles, vaccines, electronics, or high-speed rail, the system that is meant to fulfill society’s needs is blocked from doing so. Once these clogs are cleared, there’s no reason to believe we won’t supply ourselves with the high-pressure spray of ever-improving goods and services that is the American birthright. If there appears to be a problem regarding scarce resources or conflicting values, we should just innovate our way out. Lab-grown meat means we get to have our animals and eat them too. This isn’t the focused solar-communist prediction about the increasing efficiency of photovoltaic modules, it’s an all-purpose ideological faith in novelty.

Klein and Thompson are skilled presenters, and Abundance is hardly the worst thing for sale at the airport. If anyone can persuade America’s selfish liberal homeowners to stop thinking of every new housing development within their real estate market as a personal attack, it might be these two. But overall, their thinking represents a step back for a society that, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, fought for the space to think about our problems structurally. As the Obama administration hit the limits of its own politics of progress, Americans on the left (to whom Klein and Thompson explicitly direct their book) questioned whether economic inequality, racism, misogyny, and environmental destruction really were in the process of evaporating, as progressives had hoped. And if not, why not? Perhaps innovating to meet everyone’s needs was not truly what the system was for.”