Elections

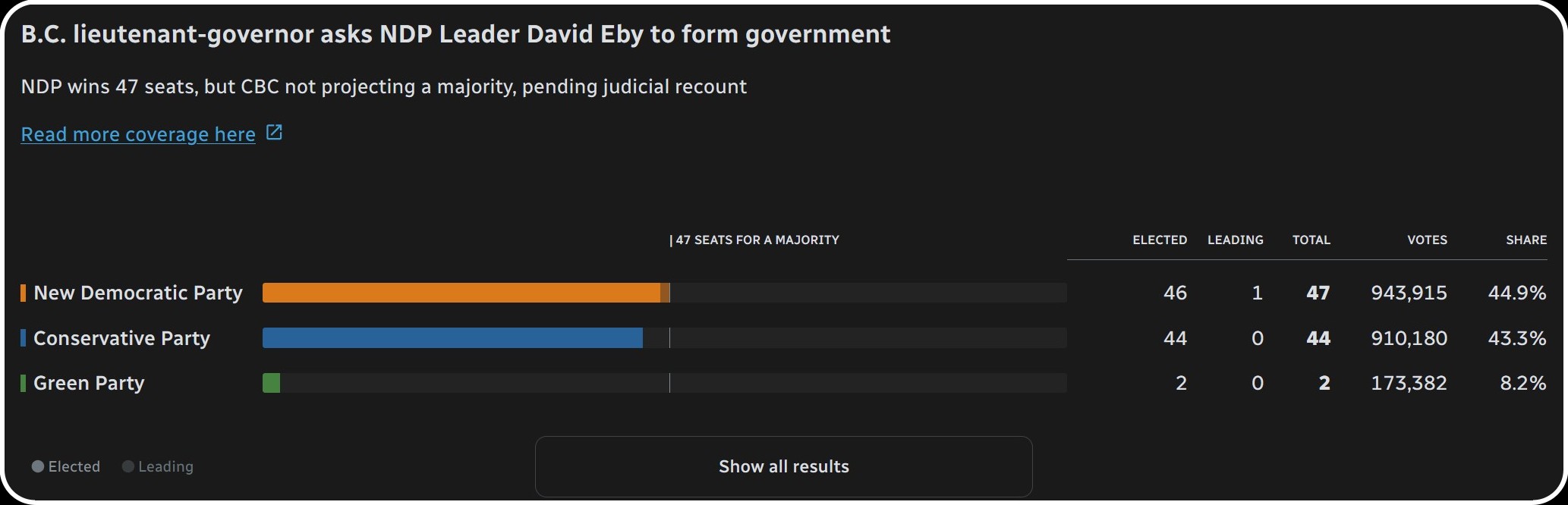

BC election results as displayed on CBC News, courtesy Elections BC.

BC election results as displayed on CBC News, courtesy Elections BC.

The current era of Indian political and cultural life began in earnest on May 16, 2014. The day that the results were announced of a tide-turning general election in the world’s largest democracy, after more than half a billion votes had been cast and counted.

A movement with populist and nationalist cornerstones, burgeoned by an unprecedented social media campaign and primarily appealing to economic interests, took its opportunity to bring the BJP and its stalwart figurehead to power. The National Congress and their allies could barely put up a fight; their more secular vision hardly enough to hide their historical shortcomings against endemic problems (like corruption) blighting the political class.

Modi’s ascension was also enabled by the media, which was largely corporately controlled and friendly towards politicians who would benefit the socioeconomic elite. The narrative of the inevitable orange wave was paralleled across all major networks. The excusal of extremist tendencies and historical whitewashing was depressingly familiar.

I was walking along Mumbai’s Marine Drive that day, the waters of the Arabian Sea calmly swirling around its tetrapods. Television screens could be glimpsed through storefront windows and opened doors, showing updated parliamentary seat counts as the results rolled in. It was a dry day across the nation and an air of jubilation could be sensed in the humid atmosphere. People in the country’s largest city were celebrating.

All of this felt odd. There are times in one’s life when the feeling of hypersanity peaks. The belief that you are the only one in the vicinity who can see things clearly seems to take over. This was one of those moments. I was decidedly not content, even sad, for the prospects of what such a movement could do to a nation that had struggled since independence with colonial legacies and sectarian violence. Some of those fears have since been realized. Although whenever elections roll around, I tend to gravitate towards a similar mind space. There is always a debate around the pros and cons of each party’s policies and records, and each politician’s rhetoric and stated beliefs. All of that is fine; being critical of authority is essential. But what is alarming, for those of us humanists who cannot disregard the discarding of social welfare in all its forms, is the scapegoating of specific groups, politicization of non-political realities, and malice for the sake of malice. The fact that some so easily latch onto propaganda, conspiracies, and become apologists for hateful paradigms is a worrying trend.

– / – / –

Swings of the political pendulum are perpetual. Back in 2014, the BJP in India saw their seat count more than double as their alliance won a majority. The next year, I watched from the UK as a comparable shift occurred in Canadian politics, with Trudeau’s Liberals more than quintupling their seat count as they uprooted the Conservatives to grasp their own majority for the first time in several election cycles. The year after, not soon after I landed back in Vancouver in the Fall of 2016, coverage of the now infamous rise of Trump was in full flow. The GOP would stunningly take the Presidency while retaining control of both the House and Senate. All this to highlight a common, intuitive, and frustrating thread in life under democracy – a changing of the guard is inevitable when leadership hangs around for a while, no matter its level of success.

The engaged electorate tends to be reactionary.

That brings us to now – 2024 in Canada, as elections abound. BC, New Brunswick and Saskatchewan have already headed to the polls in October, with Nova Scotia to follow next month. The specter of the 2025 federal election looms large; even though the provincial parties are independent of federal ones, many are leveraging associations with their federal counterparts in a political branding game. Identity politics, personal and societal, are now dictating election results across the country. And boy is the hypersanity peaking.

Here in BC, a unique transformation has occurred in quick time. A Liberal MLA, expelled from his party for denying climate change, joined the Conservative caucus. Within a year, the Liberal party’s support imploded thanks to a spectacularly miscalculated name change (to ‘BC United’) and internal kerfuffles on how best to manage the decreasing popularity of federal Liberal policy. Their voters fled, making their allegiance to the newly surging Conservatives clear. (A repositioning in support not surprising for those who understand the BC spectrum. The provincial Liberals were center-right, while the Conservatives are further right wing. More aligned with the former than the center-left incumbent NDP.) Meanwhile, the expelled MLA gained the Conservative party’s leadership and cozied up to his federal counterparts. And though it took ten days to find out in a closely contested election, the results of this month’s vote have left the BC legislature split down the middle. The Conservatives are now the main opposition to the New Democrats.

How did the MLA respond to his party’s sudden rise? In two successive speeches, first promising explicitly to not work across the isle and refusing compromise with other parties, and second assuring the electorate that he would do his best to topple the victorious government should they refuse to follow the opposition agenda. Astonishing. But not as unforgivable as dismissing the racist and sexist remarks made by his party’s representatives, enabling conspiracies to proliferate during the campaign, and denying basic science.

But you may be thinking the rise of the blue party is not just down to a name change undertaken by an opponent. Surely there must be more to this story. There is – only slightly – but it could almost be labeled trivial. Recall how the US Republicans ran on no platform until the very last minute in 2020. Because they knew that regardless of what substance they offered, they had seventy million votes in the bank. The BC Conservatives released their platform, sans a full budget breakdown, process, stakeholder lists, or much analyzable context at all, only four days before the vote. The NDP were also late in the submission of their vision, but the party in power at least has a record to be judged against. Brands and identity were enough to guarantee a large percentage of support.

After all, and this is the crux of the matter, we are witnessing the deployment of a template that has found incredible success among populist movements worldwide. Newt Gingrich was the first to champion it in the US Congress in the 80s, but even he was borrowing from playbooks regularly used by obstructionist and autocratic regimes going back centuries. The features of the template are always the same:

- Refusal to compromise or concede on policy matters,

- Regular, frivolous legal challenges against political opponents,

- A focus on spreading misinformation; promoting soundbites no matter how easily disproven, letting the speed of spreading lies outpace fact-checking,

- An engagement with media ecosystems non-critical of your party,

- Associating political opponents with provocative terminology, and

- Anchoring your movement to personalities, not policy.

This template is also emblematic of those parties and politicians unwilling to truly govern. To move forward in service rather than obstruct for optics’ sake. When democracy is not working for you, you abandon your commitment to it. The last bullet, in particular, is what creates cult-like followings like we have seen south of the border since the rise of the Evangelical Right through the post-Regan years and the Tea Party movement. Trump is only the latest figurehead, with many preceding him and many more to come. This negative approach has also been exacerbated by the deep polarization incubated by online spaces. In the twentieth century, it was television that allowed the above intimidation to succeed. Now, it is social media and its nurturing of mass credulity. A capitalization on our proclivity to engage with inflammatory content for the sole purpose of increasing short-term profits.

So, the seemingly overnight lurch to a more formalized right-left binary in BC politics is only the latest, expected outcome in a broader political project. The above tactics are used by many in the political sphere, though more prominent on the right. Right-wing messaging against government, science, academia, and the elite goes back ages. As we have all become accustomed to picking and choosing our media bubbles, drawn in by the outrageous, we have also all deferred to simpler narratives – preferring the entertaining and comforting in policy proposals, over the complex or effective solutions that may address systemic issues. I do not see a mitigation of this reality until the profit motive is removed from essential online spaces, education, or the political process. Abundant capital and nonsensical decoration go hand in hand.

Political commentators have pointed to the recent rhetoric deployed by parties across the spectrum in Canada in recent times and referred to this modern discourse as being ‘Americanized’. But the undercurrents are global. Aside from polarization sweeping large swathes of the Western world, we are also witnessing a stagnation in democratic engagement. Negativity, as mentioned above, dissuades voters. When one set of parties focuses their campaigns on threats of certain social groups, the incumbent government, elites of all kinds, rival states, or nebulous menaces, they are playing on easily manipulated fears. When those fighting this messaging focus their campaigns on the threat of the populist movements, they are also creating a foundation of fear. The two are not equivalent, but they do likely impact turnout.

The BC election saw less than 60% of eligible voters participate. Just like the majority of provincial elections in Canada since 2000, and many across a planet that has seen turnouts decline consistently since the post-war period, the largest voting bloc was comprised of those who did not cast a ballot.

– / – / –

Those acquainted with world affairs are aware of this year’s importance to global politics. Half the world’s population is eligible to vote in 2024. Results so far, many disputed, are already aligning with the populist fashions of the last decade.

In places where deep social divisions have been buoyed by toxic leaders and social media bubbles pushing people further apart, elections are now becoming a story of heightened violence. Democracy requires a commitment to more humanistic principles; hate can only erode its strength.

I am certain that most of us feel that we are not well represented by these binaries, nor by extremist rhetoric espoused by those on the fringe. That we require certain standards from those we pedestal and are comfortable removing them from elected office should they abdicate their responsibilities to their fellow humans. I am also hopeful that we can bring more to the political process than inclinations towards party colors and personalities; that our engagement is reciprocal, demanding more than just catchy messaging and hyperbole from those who seek to lead us.

For now, and with this result, I can seek solace in the fact that the group enabling all the corrosive trends above is not in power. But their movement is still thriving nationwide and there is a far more consequential campaign coming up. It is an unnerving thought that the wellbeing of so many lives can so drastically shift based on one election. The perceived stability of institutions notwithstanding, their utilization and structures vary as widely as the swings in the metaphorical pendulum. A back-and-forth that is growing in scope with each passing year.

All it takes is one brief exercise in voting to maintain, end or reprise progress. To maintain, end or reprise regression. An exercise we all need to undertake, with as informed an approach as we can muster.